Aatje Veldhoen

1934-2018

Artistic Biography by Ed de Heer

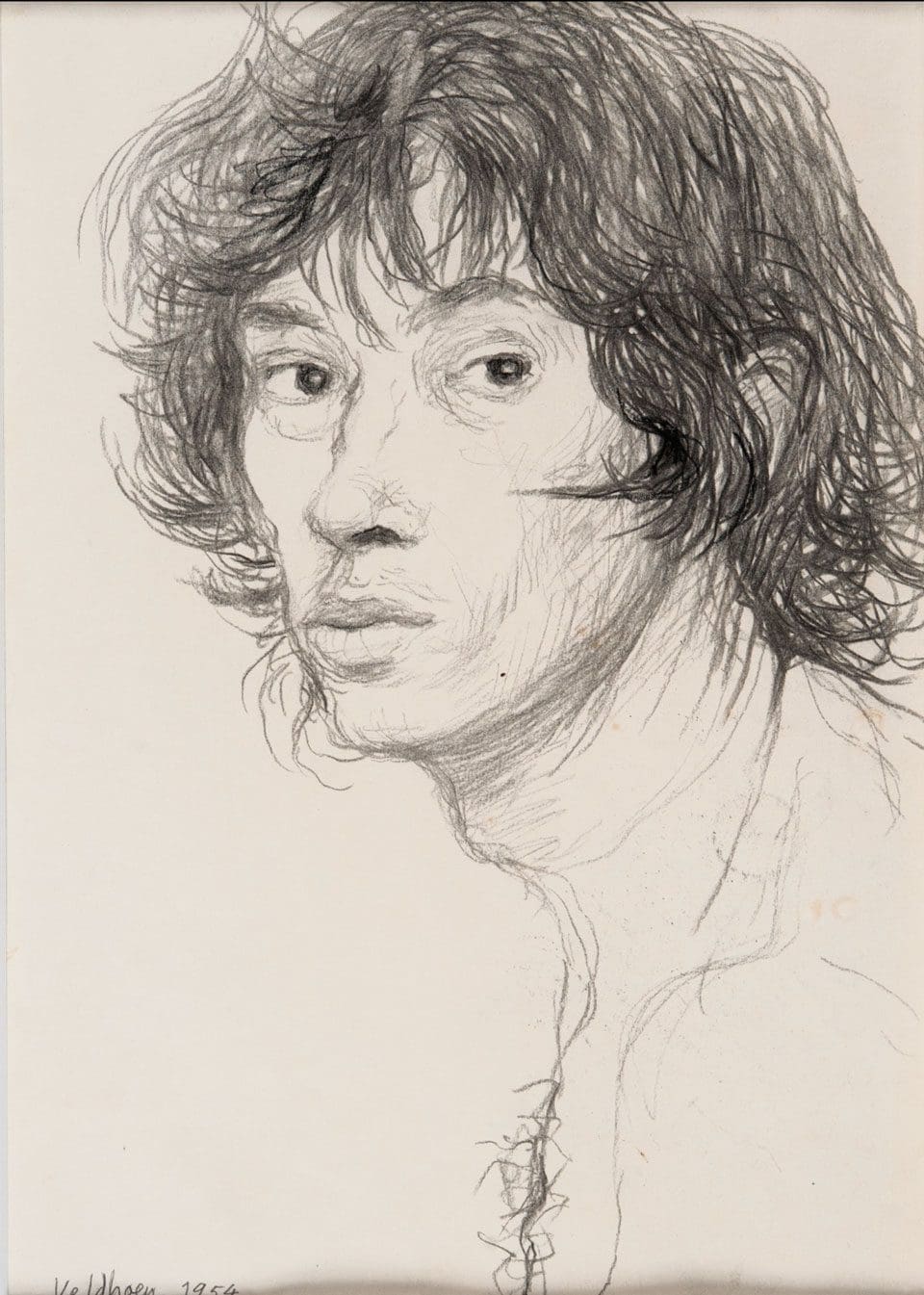

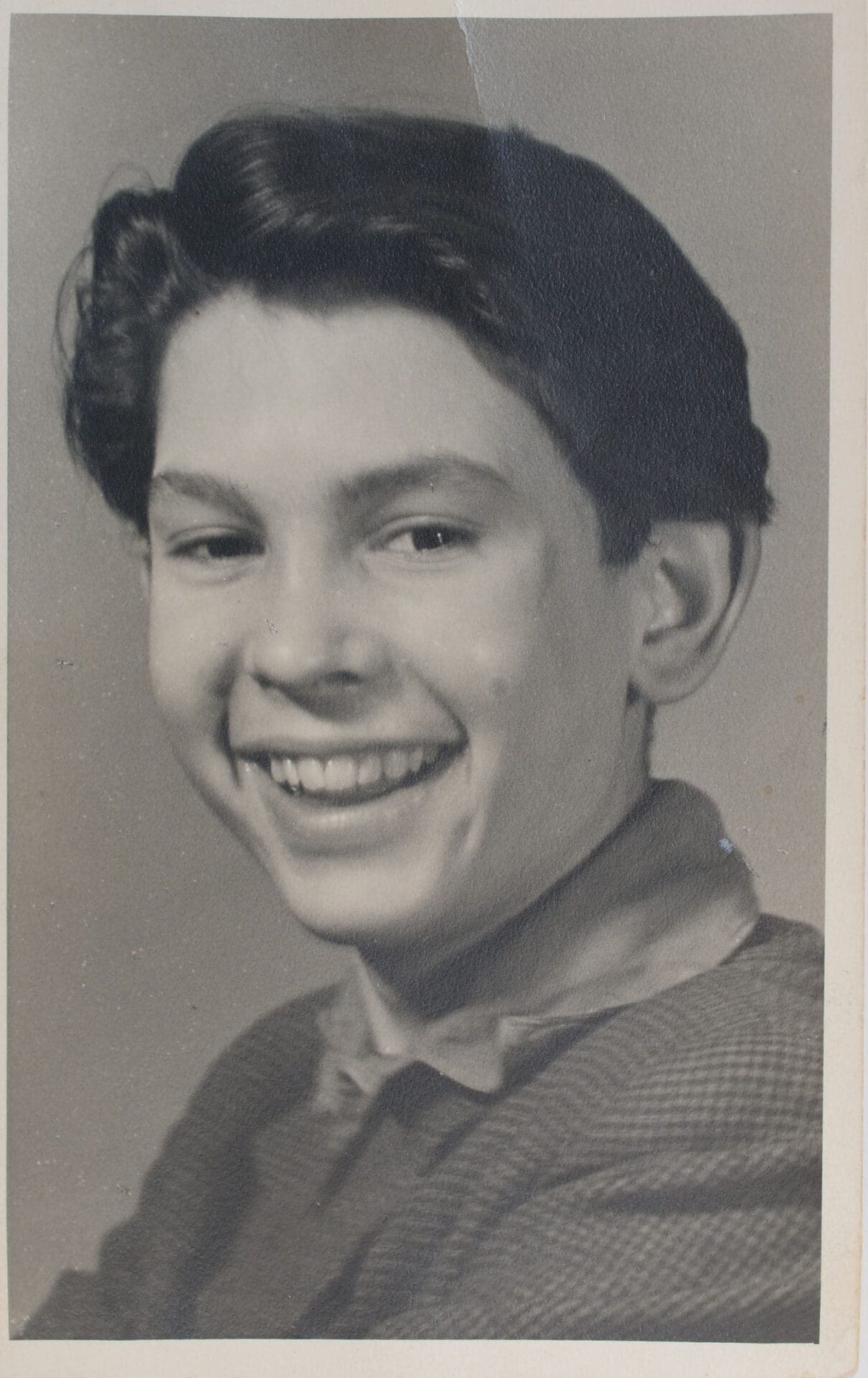

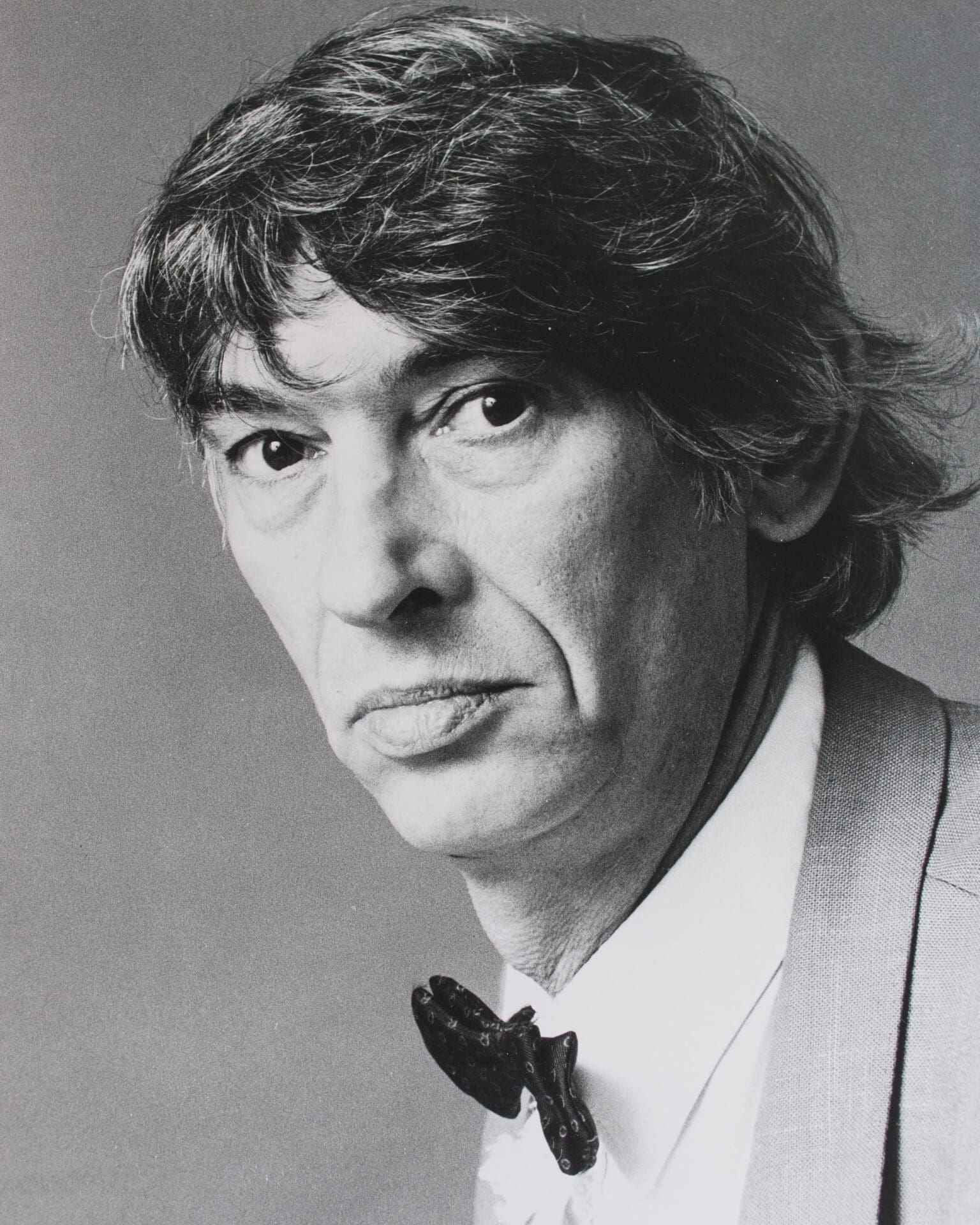

Arie Johannes Veldhoen was born in Amsterdam on November 1, 1934. His artistic talent revealed itself at an early age. His father was a painter. He made drawing and painting materials available to his son, but did not actively interfere with his artistic development. At the age of just 14, Veldhoen was admitted to the Rijksnormaalschool in Amsterdam. He received a thorough education in which a lot of attention was paid to subjects such as perspective, composition, anatomy and portrait drawing. After four years he left the training prematurely and left for Scandinavia, where he stayed for several months. Back in Amsterdam he established himself as an independent artist.

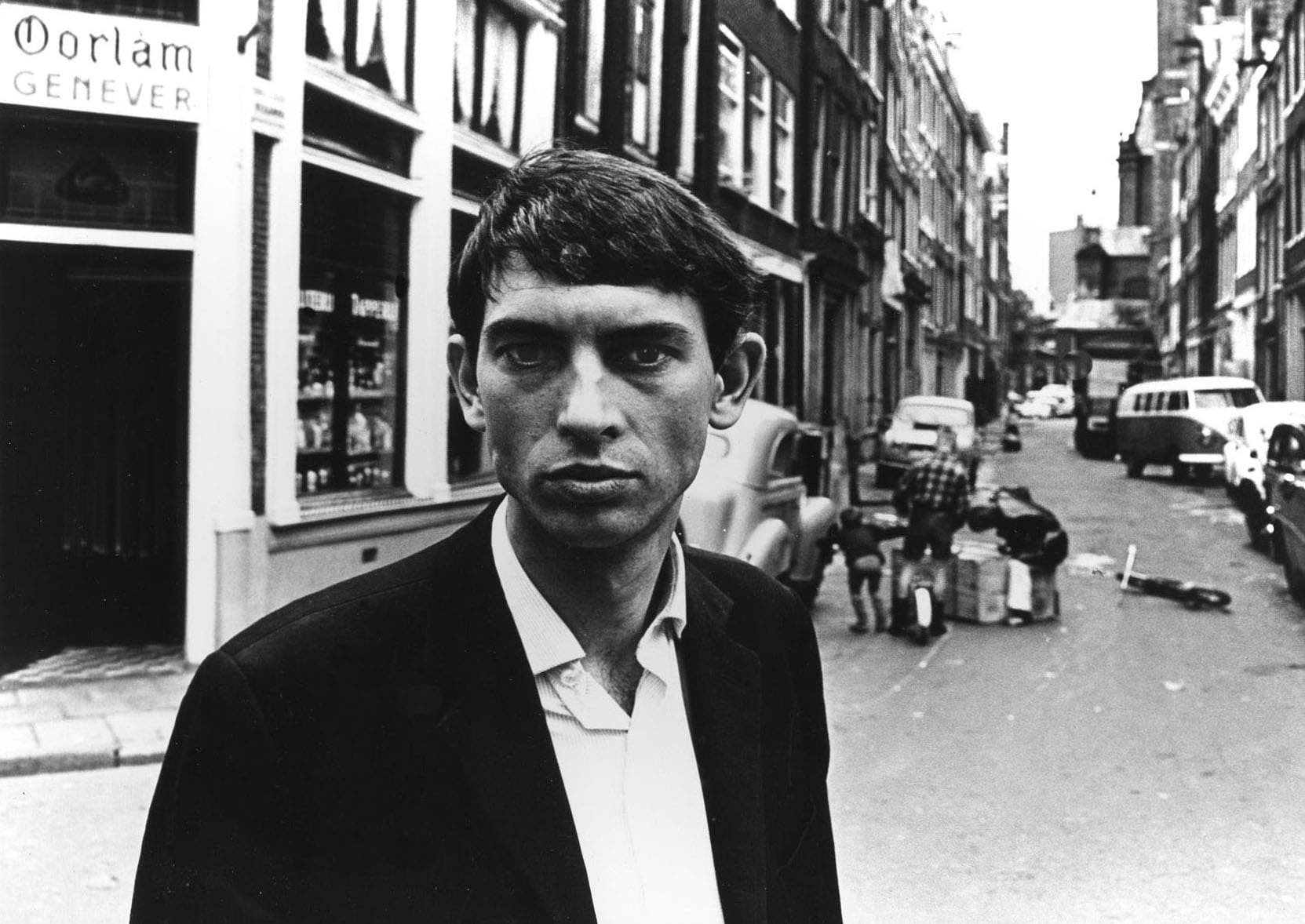

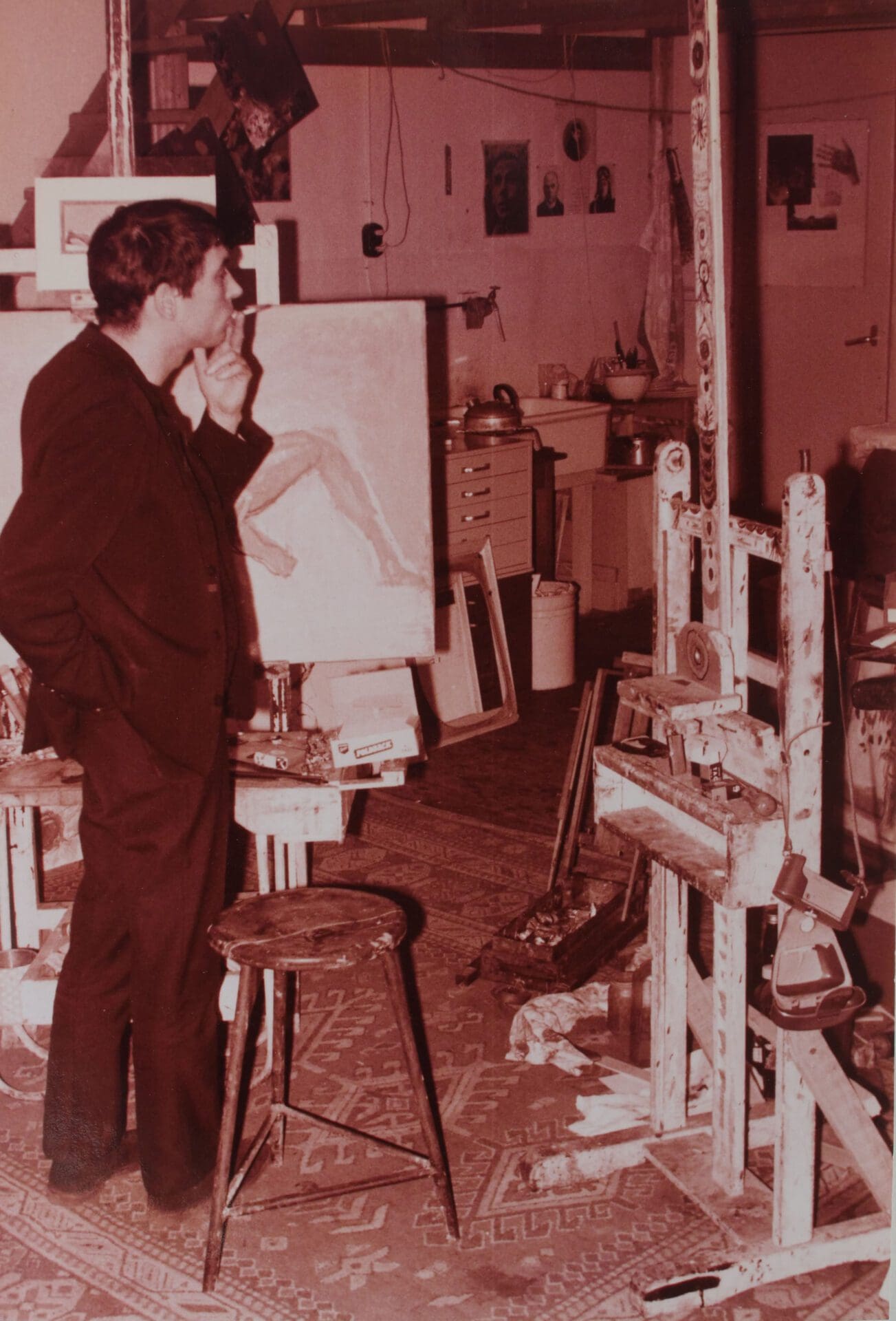

Veldhoen quickly made a name for himself as an etcher, a technique he taught himself. Although Veldhoen introduced new subjects into etching, such as his series with women in labour and victims of street accidents, it is mainly the frank, uncompromising execution and the accurate and very personal way of drawing that appeal to the imagination. Due to its themes and undisguised realism, Veldhoen’s work is closely linked to the emancipation and liberation of the individual from the oppressive straitjacket of church, state and narrow-minded bourgeois morality in the 1960s.

In 1964, in an attempt to make art accessible to a wide audience, he started the production of rota prints. The lithographs printed in high numbers on the offset rotary press, which did not differ in any way from traditional lithography, were sold for a few guilders. The project dramatically lowered the value of his work and was one of the reasons why Veldhoen stopped making prints and focused entirely on painting from 1967 onwards. Only in 2000, when he was allowed to work in Rembrandt’s former studio for a few weeks, did he start etching again.

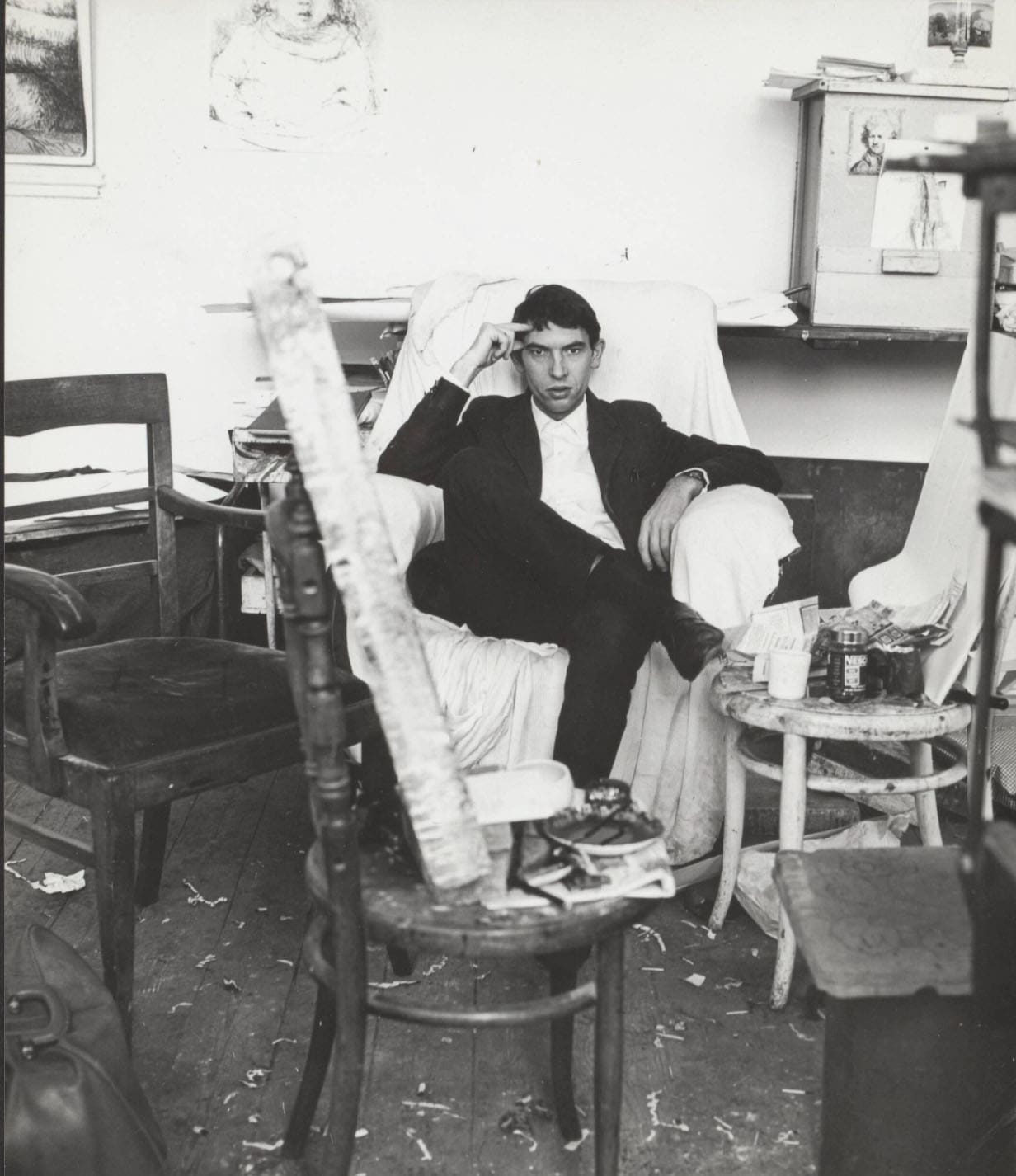

Veldhoen received recognition as a painter early on. In 1955 he was awarded the Royal Subsidy for Painting, a cash prize that he would also receive in 1957. Veldhoen focused from the very beginning on depicting visible reality and, with the exception of a few isolated experiments, has always remained faithful to figuration. His work exhibits a unique variety of themes, but of all the subjects he painted, the woman was dearest to him. The candid way in which Veldhoen portrayed his subjects led to conflicts and legal proceedings on several occasions.

Photography plays an important role in Veldhoen’s work. He used photographs as a memory aid or to record short-term situations. In 1977 he was introduced to the creative possibilities of Polaroid photography. He saw the technique as a fast and effective way to make preliminary studies for his paintings and started making manipulated Polaroids in the 1980s, of which he made around 3,500. Veldhoen was also active as a sculptor. He also painted ceramics and made tile paintings.

In 2004, Veldhoen lost control of his right hand as a result of a stroke. However, the urge to draw was so great that he already started drawing with his untrained left hand during his stay in the rehabilitation centre. The driving force behind Veldhoen’s artistry was his insatiable curiosity and social engagement, his compassion for the downtrodden fellow man and his deeply rooted aversion to authority, church and royalty, which have their origins in his parents’ communist background and his own war experiences.

Veldhoen was successively married to Lotje Ruting, Kabul Mohammed and Cristi Kluivers and has eight children. He lived with Hedy d’Ancona from 1998 till his death in 2018. Text by Ed de Heer.

Personal Biography by Natasja Rietdijk

The art of Aatje Veldhoen is alive! It is both intimate and bold, profound and witty and shows a keen eye for the human condition. Veldhoen’s prints, paintings, sculptures and photographs have found their way into the collections of leading Dutch museums and are shown in prominent exhibitions throughout The Netherlands.

Arie Johannes Veldhoen, soon to be called Aatje, was born in the heart of Amsterdam, the son of a painter and a schoolteacher. He was five years old when WW II broke out. His personal suffering and the death and devastation around him shaped him for life and influenced his art. His parents’ communist convictions and their antipathy against colonialism, militarism and royalty, were equally defining factors. His mother supported the family with her teacher’s salary. Arie sr., a portrait artist and painter of Amsterdam scenery, left the family soon after the war, to move in with his model mistress. He seemed to regret this decision and often visited his family. He died at the age of forty-eight of a heart attack.

Aatje, a perceptive and quicksilver child, grew up quick. As his talent was apparent from an early age, he was encouraged by his parents to become a painter. At fourteen he enrolled himself in the Amsterdam school for art teachers and also left this school prematurely, self-confident about his talent and with little patience for the formal, academic side of the métier. He did learn how to draw the human bone structure; skeletons would show up in his work throughout his life.

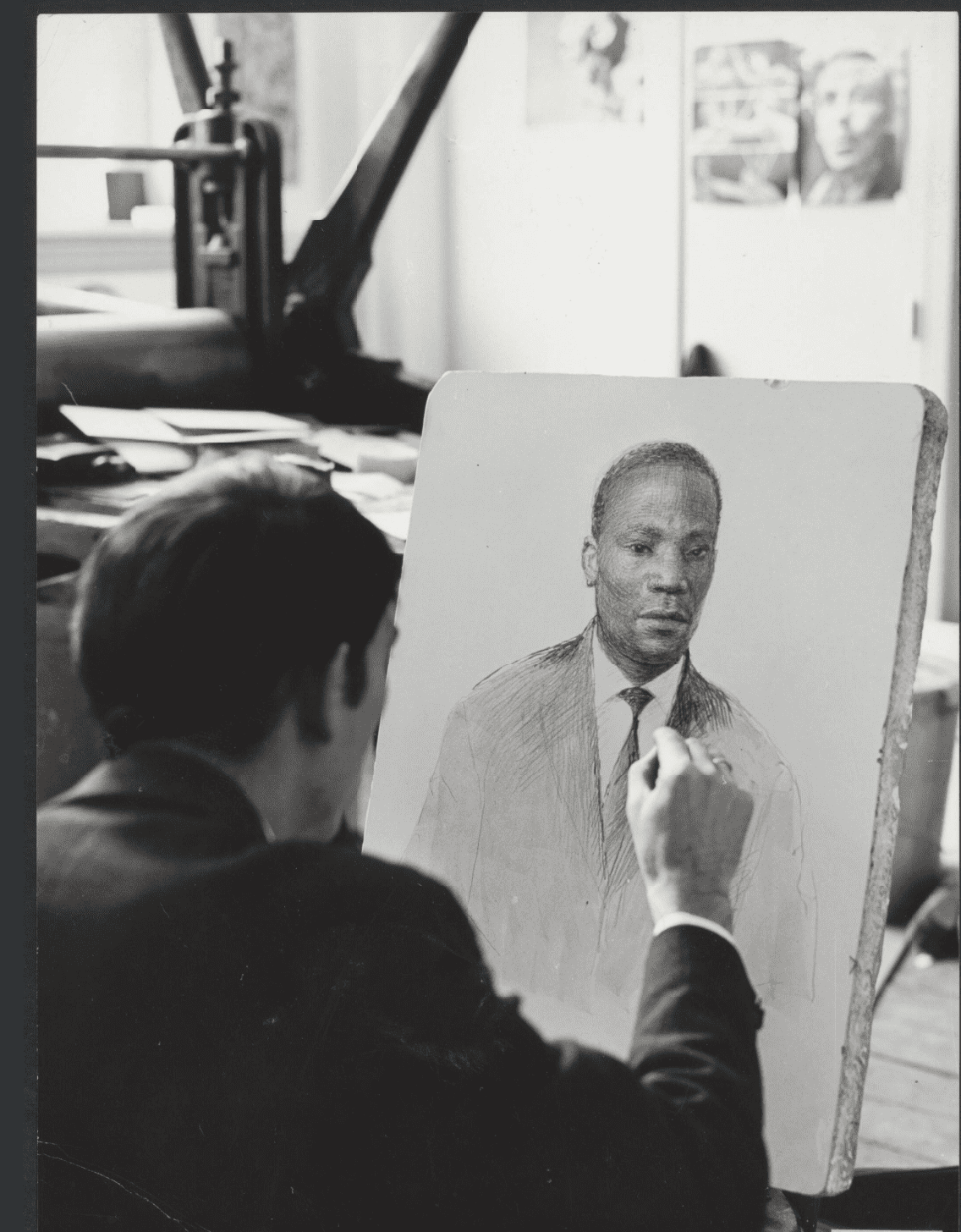

In 1956, Aatje married Lotje Ruting, a kindergarten teacher who lived a few doors down from him at the Bloemgracht. The strongly socially conscious Lotje, grew up in foster homes because of her parents’ subversive activities during the war and, later, her mother’s bohemian lifestyle. She modelled for Aatje, became pregnant and the two got married, after which three more children were born. Selflessly, Lotje facilitated Aatje’s artistic development which was soon rewarded by the Dutch Royal subsidy for promising young artists, twice, in 1955 and again in 1957. Aatje’s father had instilled a deep sense of reverence for Rembrandt in his children, taking them on trips to the Rijksmuseum regularly. Not long after starting his life as an independent artist, Aatje began to experiment with etching and lithography and in time came to emulate the great Dutch master both in technique and emotional charge. Aatje’s arts subjects were the common man and woman – and the uncommon one. People he found willing to pose for him were his neighbors and friends, the local greengrocer and his wife, professionals, often in their job’s attire, the first black immigrants, actors, writers, a transvestite, a drug addict. Clergy members, royalty, politicians, big oil and big business (weapon dealers and cigarette manufacturers) would find themselves the targets of his fiercely provocative protest art throughout his life.

The extraordinary quality of Aatje’s work and its subject matter stood out from the beginning. He received permission from leading heart surgeon Boerema to witness live operations in the Wilhelmina Gasthuis hospital. In a white medical assistant’s outfit, he was also allowed to draw in the maternity ward, hiding his copper etching plate behind a wooden slab for notetaking. The births were later matched with the conceptions: he asked friends and their wives to pose for him while making love on the bed in his Lauriergracht studio. This art was met with indignation from religious authorities and conservatives. But no one questioned the quality of the young artist’s work.

In 1964, a new technique was shown to Aatje by a local printer; the offset printing press. The machine, with the brand name Rotaprint, considerably speeded up the laborious process that Aatje had, up to then, done by hand. It inspired him to start making his own “Rotaprints”; affordable art “for the masses”, hoping his colleagues would follow suit. His friend Robert Jasper Grootveld, performance artist and visionary, came up with the idea to distribute the prints from a handcart in the streets of Amsterdam. The price was set at 3 guilders, about the cost of a week’s groceries at the time. The often-explicit subject matter of the prints led to nationwide fame and notoriety. Sales were great, but other artists failed to follow his example and Aatje’s one-man print revolution resulted in financial ruin, as the value of his work plummeted. The experiment led to some tensions between Aatje and Lotje, and also to a court case, which received nationwide media coverage, including on the new medium of television, making Veldhoen the first Dutch artist ever to be convicted for his art.

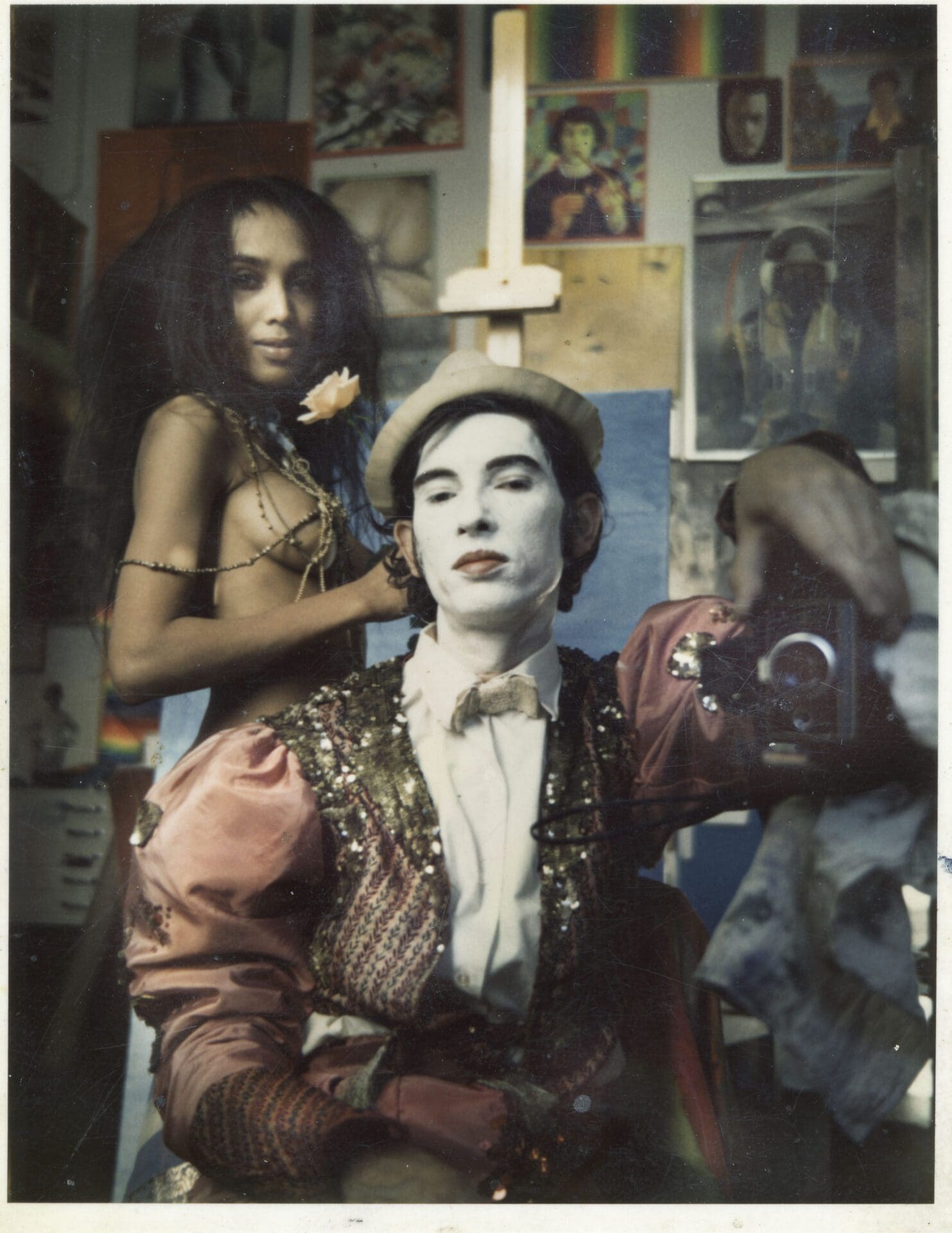

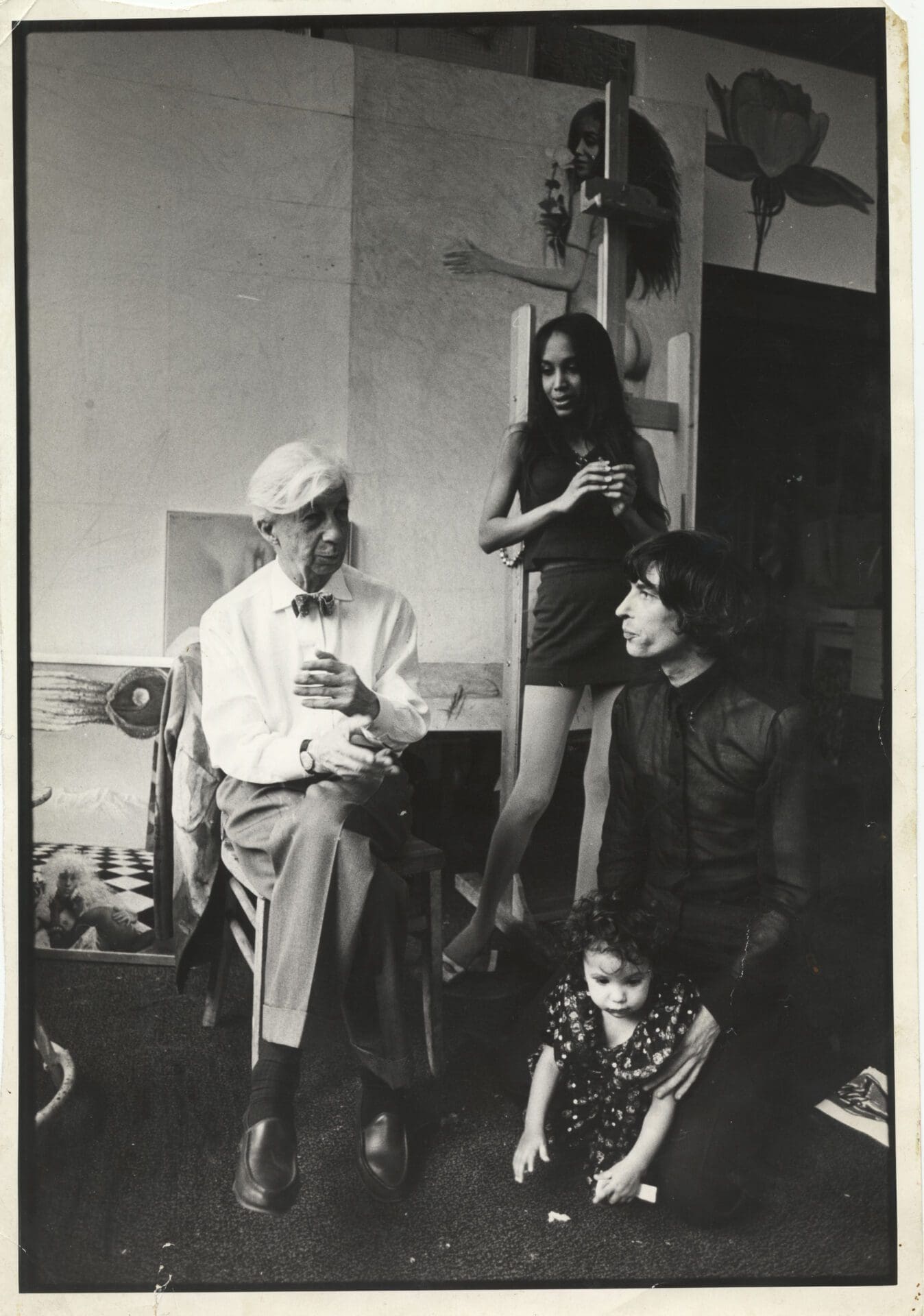

In 1967, Kabul Mohamed, a slender beauty of mixed African and Asian descent, raised in Cambodja, who studied photography in Bonn, visited Veldhoen’s studio and the two fell in love. After a heart-wrenching period, Aatje left Lotje and the children (destitute) and moved into his Lauriergracht studio with Kabul. The couple fled Amsterdam for a six month stay in Morocco, where Aatje took up drawing and painting again, and did not touch the copper etching plates he had brought with him. Back in the Lauriergracht, their first child was born in 1968. After the birth of their second daughter, the couple moved to an apartment plus studio in Amsterdam Noord, across the IJ river, where another daughter was born. Veldhoen‘s art transformed both in subject matter and technique as a consequence of the new relationship which zoomed in on the visual beauty of the couple and their love and family life. The hippy zeitgeist and the use of drugs sometimes show on the polaroid pictures that Veldhoen began making during this period and which he also used to paint large, photorealistic and often explicit paintings. This art did not generate enough income and Aatje had to enroll in the BKR program which offered artists a modest allowance in exchange for their work. Aatje fought his poverty by lashing out at the power elite both in his art and in interviews, which led to more trouble with the authorities. The couple let their hair down but grew thinner and more isolated. Kabul’s mental health deteriorated and their relationship became unsustainable.

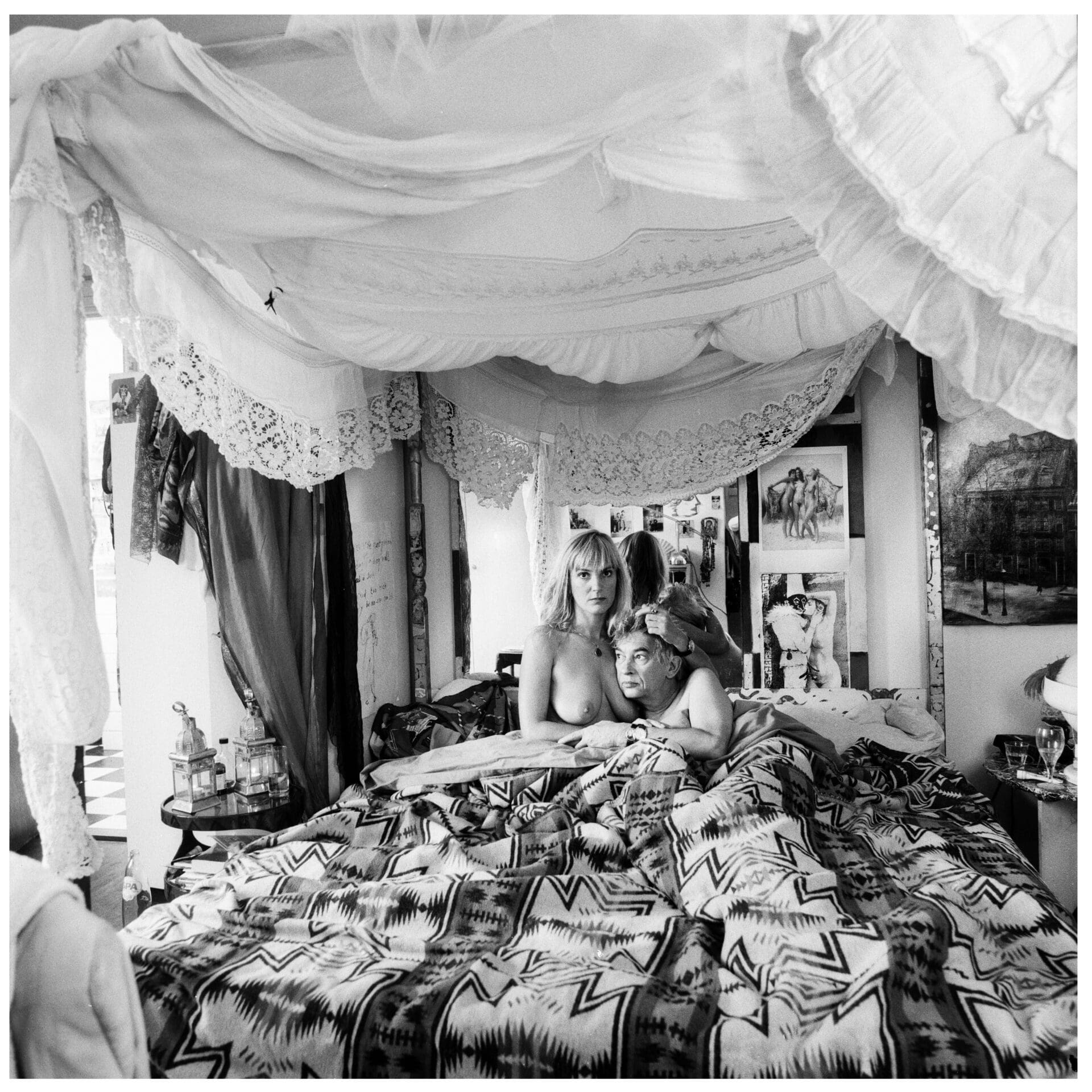

At an exhibition of the Universal Moving Artists, an artist collective, in the Amsterdam Stedelijk Museum, Aatje was struck by the uninhibited performance art of buxom young blonde Cristi Kluivers, a photographer from a small Dutch village, who danced naked on a stage. Their encounters led to a relationship and a definite separation between Aatje and Kabul. Cristi moved in with Aatje and took over the care of his three young daughters. Pictures of the wedding ceremony of Aatje en Cristi in Amsterdam Noord, in 1978, show Cristi’s pregnant belly bulging naked under her hippy wedding dress. A month later their son was born. Cristi became an energetic model for Aatje as well as his business manager and was often successful in securing exhibitions and selling Aatje’s work.

The couple welcomed other women into their lives as well as in Aatje’s art. Associations were formed with other artists, at the artists’ colony of Ruigoord, outside Amsterdam, where drugs were used and playful, creative happenings took place in an idyllic scenery. Together with some colleagues and his eldest son, he formed the Amsterdamse Palet Vereniging which exhibited sizeable rebellious artworks in public spaces and distributed satirical pamphlets in the Amsterdam streets. His private work, mostly large sized paintings in bright, expressive colors, became even more direct and unfettered during this period and he began using the newly available, fluorescent Dayglow paint. He situated his models in wide landscapes or at the beach, and painted a series of life-size nudes of his female neighbors. He also made a series of views from Amsterdam hotels, where he stayed with Cristi while working on the paintings. He portrayed Cristi and his children and colleagues and friends and their pregnant wives. After failing to persuade his mother to pose for him naked, at the age of 80, he advertised for 80-year-old nude models, finding a number of impressive ladies, one a former member of the Dutch resistance, willing to pose for him.

Aatje followed his twenty-year younger wife with growing reluctance into the Amsterdam party scene. Their exposure landed him on the society pages of newspapers and magazines and in television quizzes on national tv. Closer to home, he made a series of programs for local Amsterdam radio and television, presenting his own “Arie Johannes Veldhoen show”. He was an entertaining host who educated his fellow Amsterdammers about art and artistic morals, never wasting an opportunity to tell his audience to buy more art.

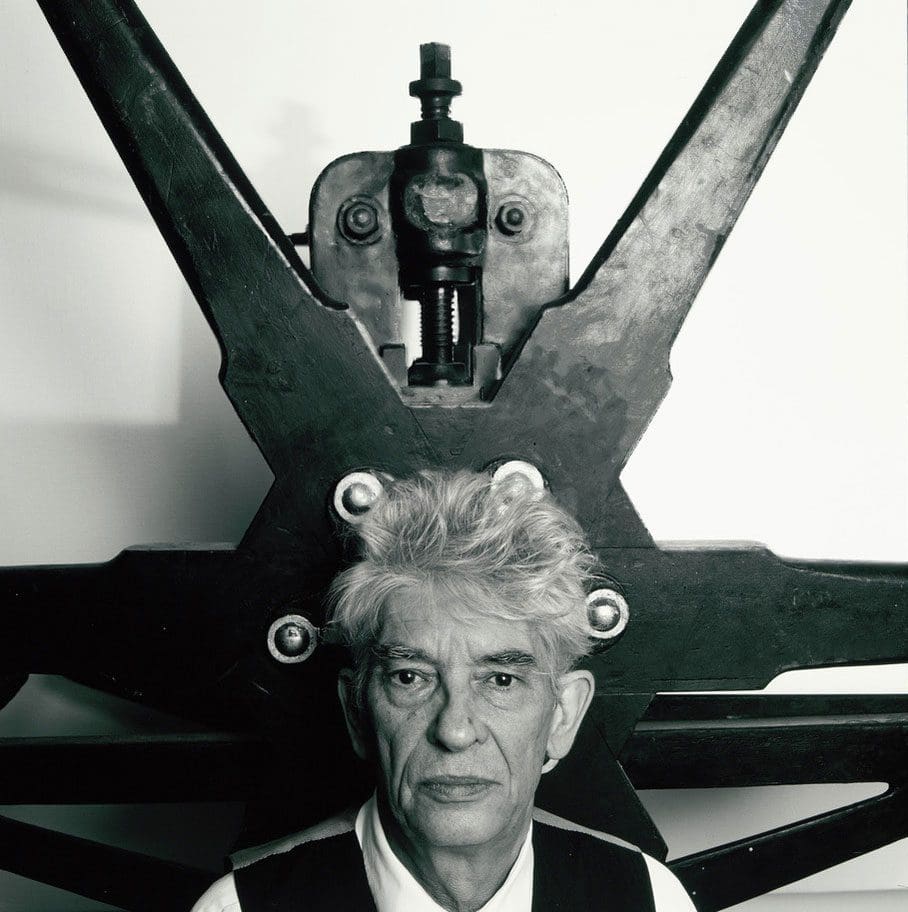

After returning to the city Centre in 1980, from Amsterdam Noord, the apartment plus studio at the Bootstraat soon proved too small. A studio with a view of the historical Nieuwmarkt (and the Waag!), provided some breathing space for a number of years as well as inspiration for many polaroids and paintings. When, in 1986, a large, early 20th century wood merchants house at the Wittenburgergracht came up for sale, Aatje and Cristi succeeded in persuading their friend Noud Vroom to buy the impressive house for them to rent it from him. The house offered plenty of room for the family of six (Aatje’s first four children had stayed with Lotje), and for Veldhoen’ s growing body of work, to which a new collection was added: sculptures. The spacious house and city garden invited Veldhoen to start carving in marble and molding wax for large bronze statues. He soldered together pieces of iron to create elaborate structures and hacked and drilled his art into sizable slabs of stone. In the more than thirty years that followed, he filled the house and garden with his art, from the souterrain floor to the fourth-floor ceiling.

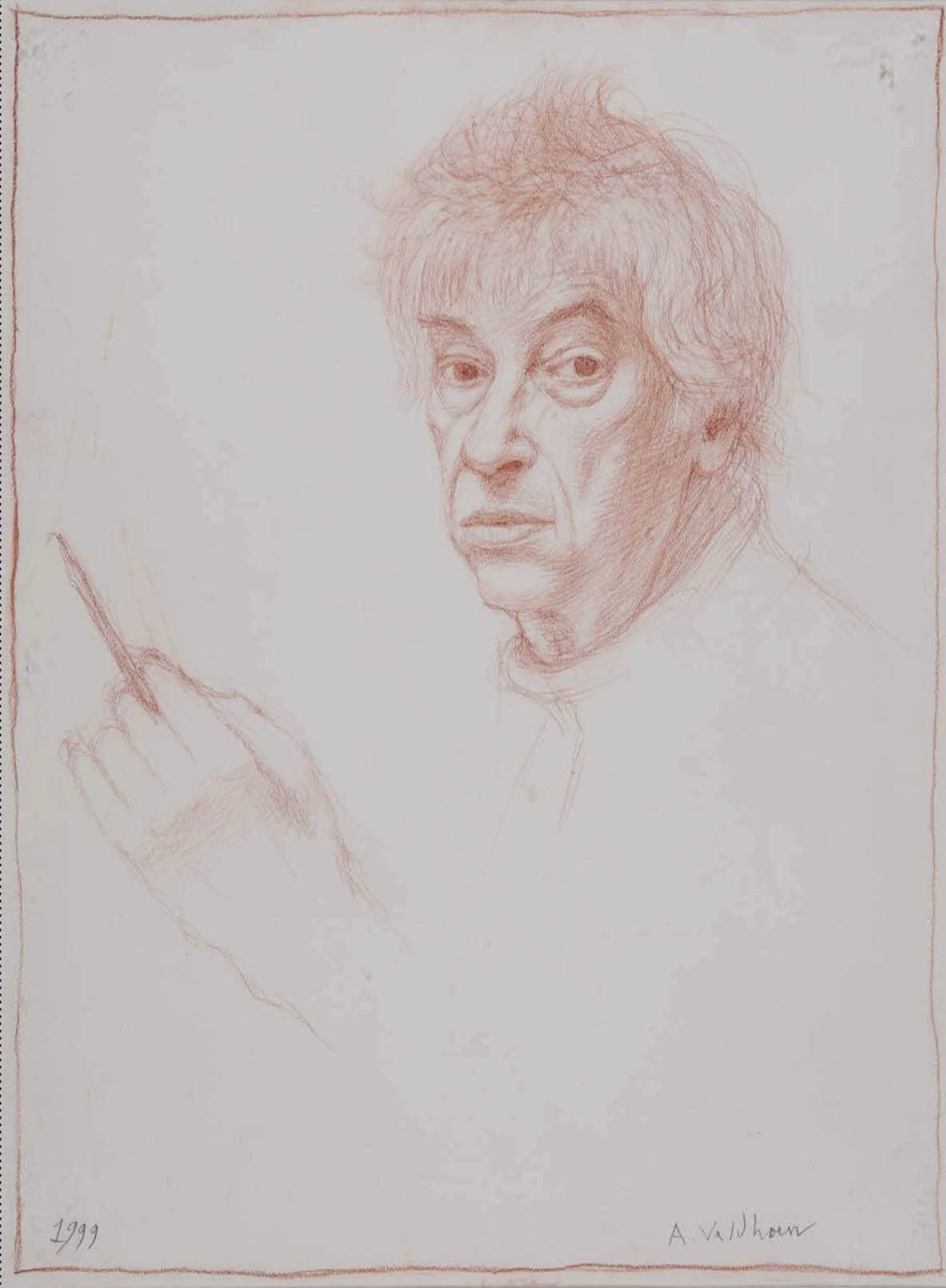

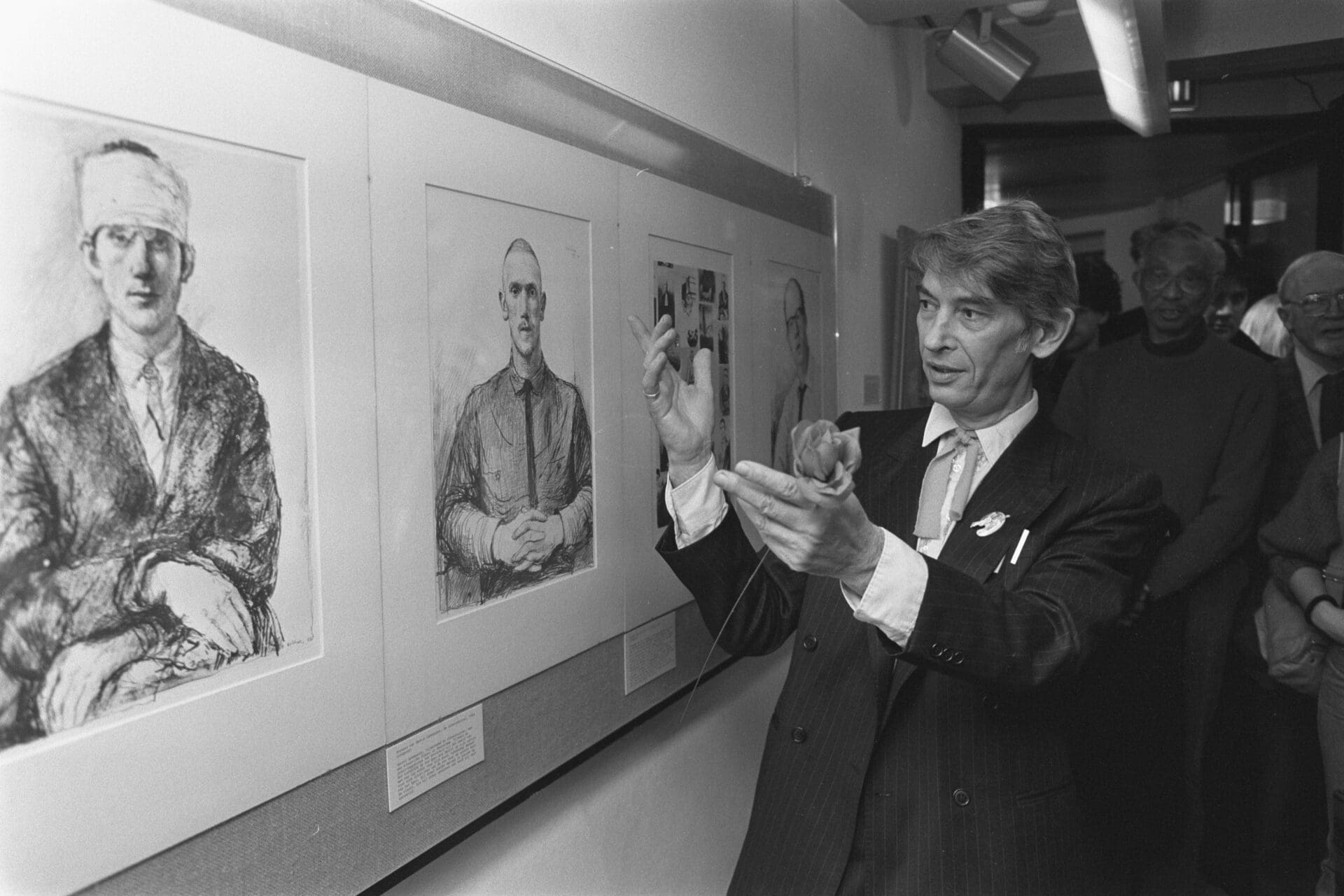

Frequent arguments and growing differences led to a tumultuous divorce from Cristi, after twenty years of marriage, in 1999. While the finesses of the arrangement where still being fiercely fought over, New Left politician, activist and second (and third) wave feminist Hedy d’Ancona was (re)introduced to Aatje. At that time, she was a member of the European Parliament for the Dutch Labour Party. Aatje, now in his sixties, this time took cautious steps and drew a fully dressed portrait of the 59-year-old former minister of Culture, public health, and sports. But after a number of dates which they thoughtfully planned out for each other, to suit the other’s mature taste, the two became a couple. Hedy kept her house at the Amstel River and led a busy life of her own and took a more distant role in Aatje‘s art than her predecessors. Her visibility, matched with his rebel reputation, drew Aatje into the spotlight once again and the couple was photographed at exhibitions, concerts and social events and frequently featured in the national and local media. Meanwhile, Aatje steadily worked on at all his forms of artistic expression. In 2000, the Rembrandthouse museum invited him and other artists to work in Rembrandts former atelier for a month. Here, with a helpful printer and a printing press at his disposal, he took up etching again, after a more than thirty year long hiatus. In the period that followed he created hundreds of new etchings that he printed in his own basement, on his most prized possession, a Krause printing press.

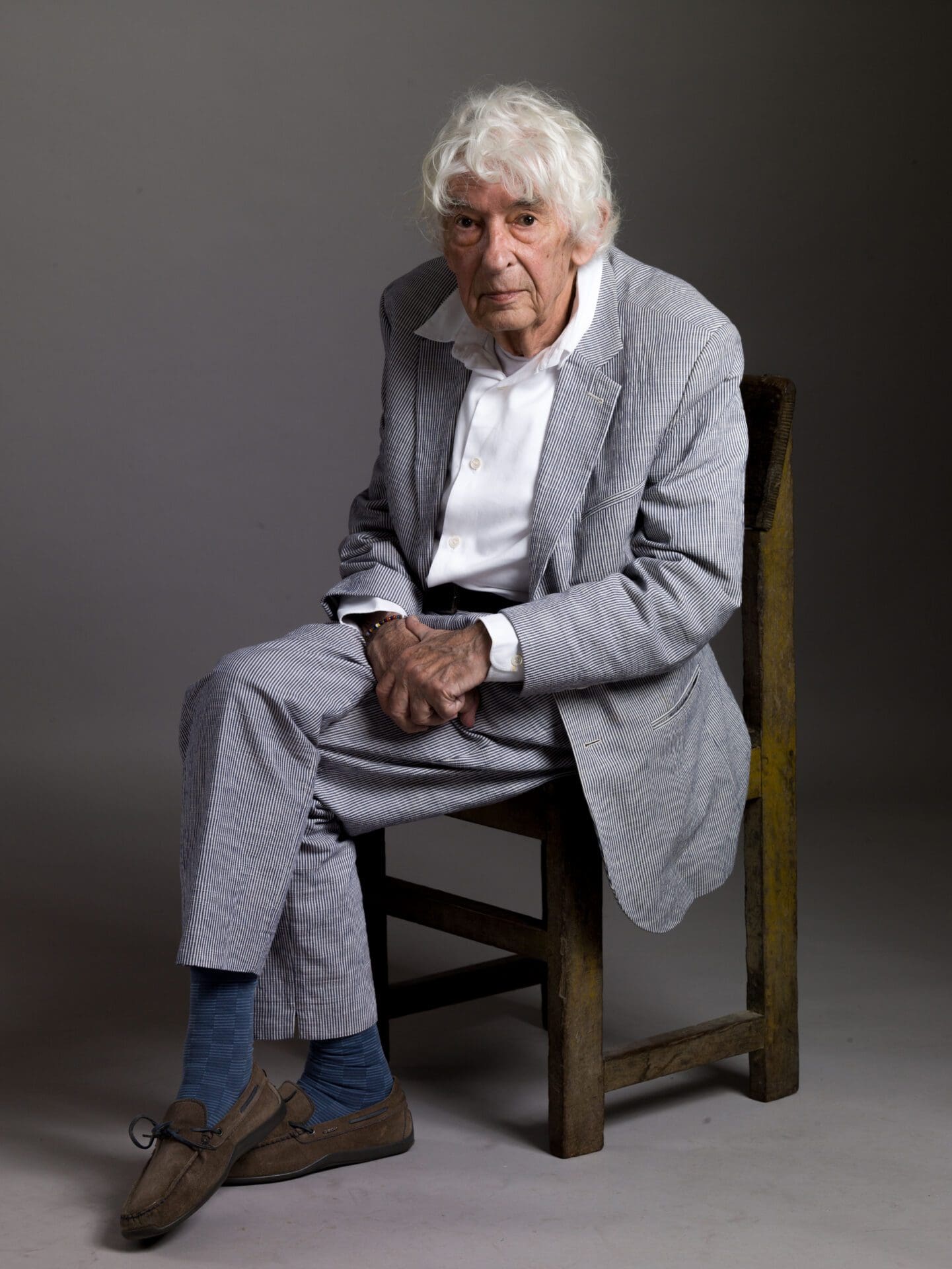

The heart attack that Aatje suffered at age fifty, did not stop him from smoking. A stroke in 2004, at sixty-nine, did, and left him half paralyzed. His speech returned with some impediments, his right leg regained its function, but his right hand, his working hand, remained motionless. Within days of hospitalization, he took up a color pencil with his left hand and drew a portrait of Hedy reading to him from Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain. Out of the hospital and with the use of only one hand (and the help of his children, some friends, amateur printers and models – and of course Hedy), he went back to work.

His eye was even now directed outward while also recording his personal life. Aatje drew the people waiting at the bus stop across the street and found his subjects in newspapers and on television. Wars, tragedies, winners and losers in sports games, beauty and royalty (still!) found their way into his art – plus the occasional bedbug, of which he found a creepy enlargement on a page of a magazine. Reluctantly leaving his house for far away holiday destinations, he drew the people and beaches and scenery there. Poignant etchings were made by him in Suriname at Fort Zeelandia. Daughters and daughters in law became pregnant and he drew them and their babies. He painted and made etchings of his paralyzed right hand. He decorated ceramics, tiles and vases with gold and platinum lusters, creating tile tableaux for his garden, his souterrain and his kitchen, as well as an extensive set of tableware. He arranged Styrofoam wrappings to make elaborate sculptures to be cast in bronze. He turned to acrylics for his paintings, which bottles were easier to open than oil paint tubes, with one hand. Still later, pastels, ink and watercolors proved even simpler mediums. He steadily kept on painting and drawing young and older models and created a colossal body of work.

On December 7th, 2018, Aatje suffered a second and fatal stroke, gradually losing consciousness. He died two days later, aged 84, in a small room on the top floor of the AMC hospital. He was laid out in his home, where, for days, friends and family crowded around the open casket in which he lay majestically, surrounded by an abundance of flowers and his art. He was cremated at Zorgvlied, on December 15th, a very cold, winters day.

The house, an artwork in itself, with its decorated ceilings and doorposts, was emptied and sold, the sculpture garden dismantled. His work found its way to museums, collectors and his descendants.

For Aatje, a person who loved his art was a friend. He put into his art that which was vital to him. This vitality still jumps from Aatje Veldhoen’s artworks to the viewer, keeping him and his art alive!

© Natasja Rietdijk 2023 Amsterdam, The Netherlands