All complete 718 graphic works are in the collection of the Rembrandthuis Museum Amsterdam. More than 150 etchings are in the Rijksmuseum. The Stedelijk museum Amsterdam owns 100 lithographs.

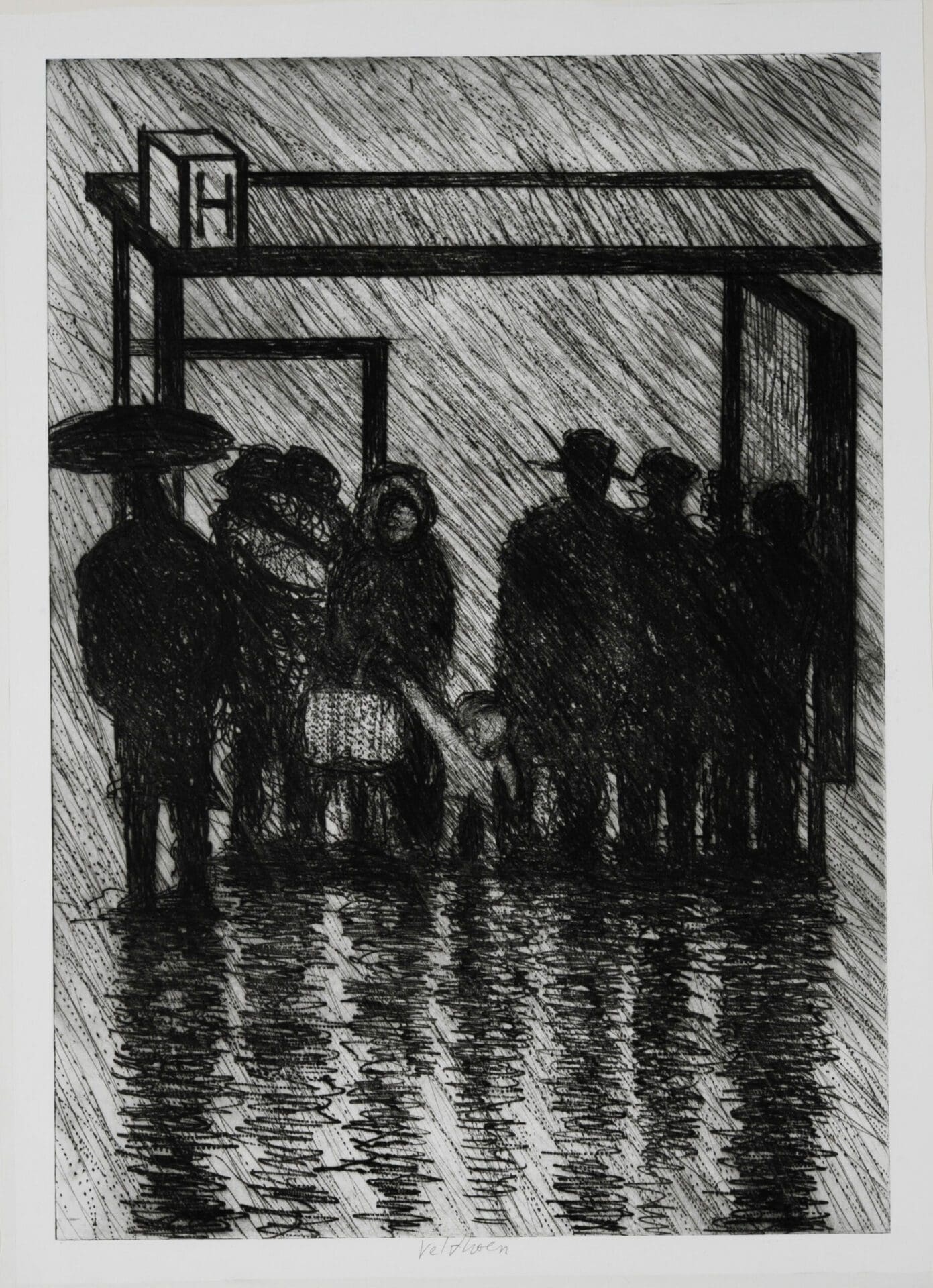

By Ed the Heer: At just fourteen years old, Veldhoen was admitted to training as an art teacher at the Rijksnormaalschool. He received a traditional training there, with a lot of attention to drawing from plaster, living model, perspective and composition. After four years he left school and established himself as a free artist. His great talent as an etcher was recognized almost immediately by the press and public. He bought his first etching press with the money he received from the Royal Subsidy in 1956.

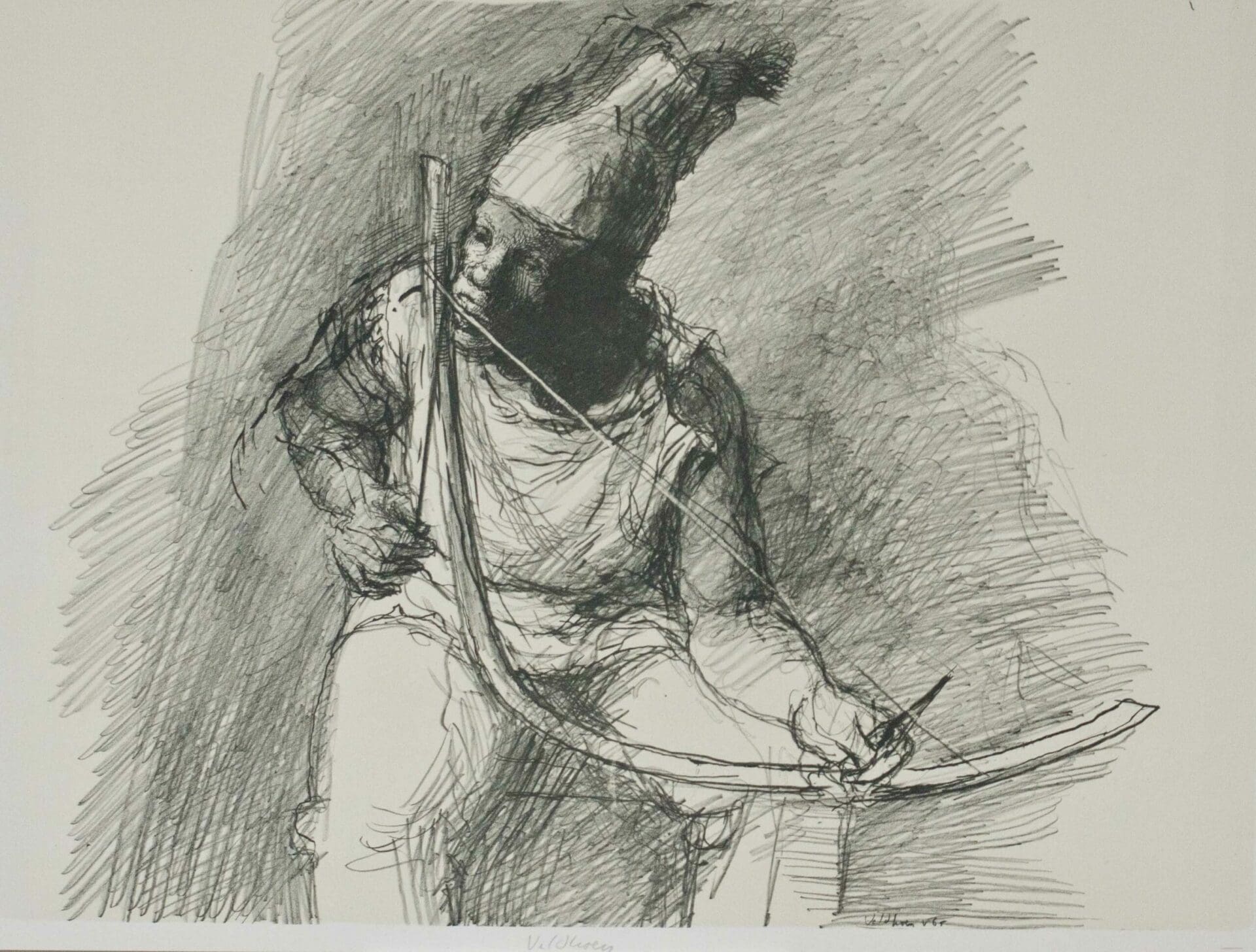

As a graphic artist, Veldhoen was self-taught. His first etchings betray the influence of masters such as Van Gogh and Picasso, but it was mainly Rembrandt’s graphic work to which he was attracted. Rembrandt’s influence is already visible in his earliest work and was mainly manifested in the variations in line thickness, which he achieved by covering parts of the etching plate during the etching process.

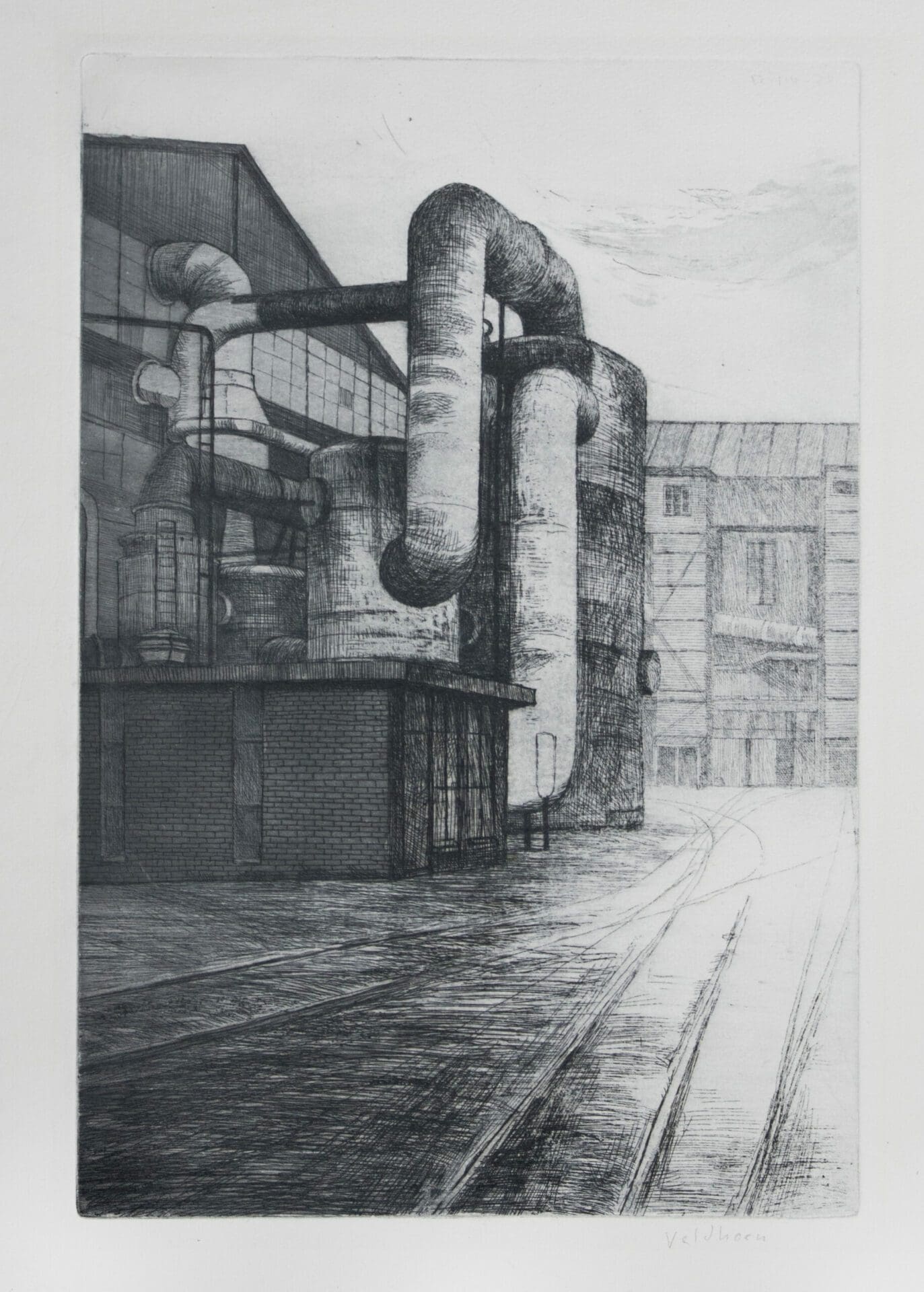

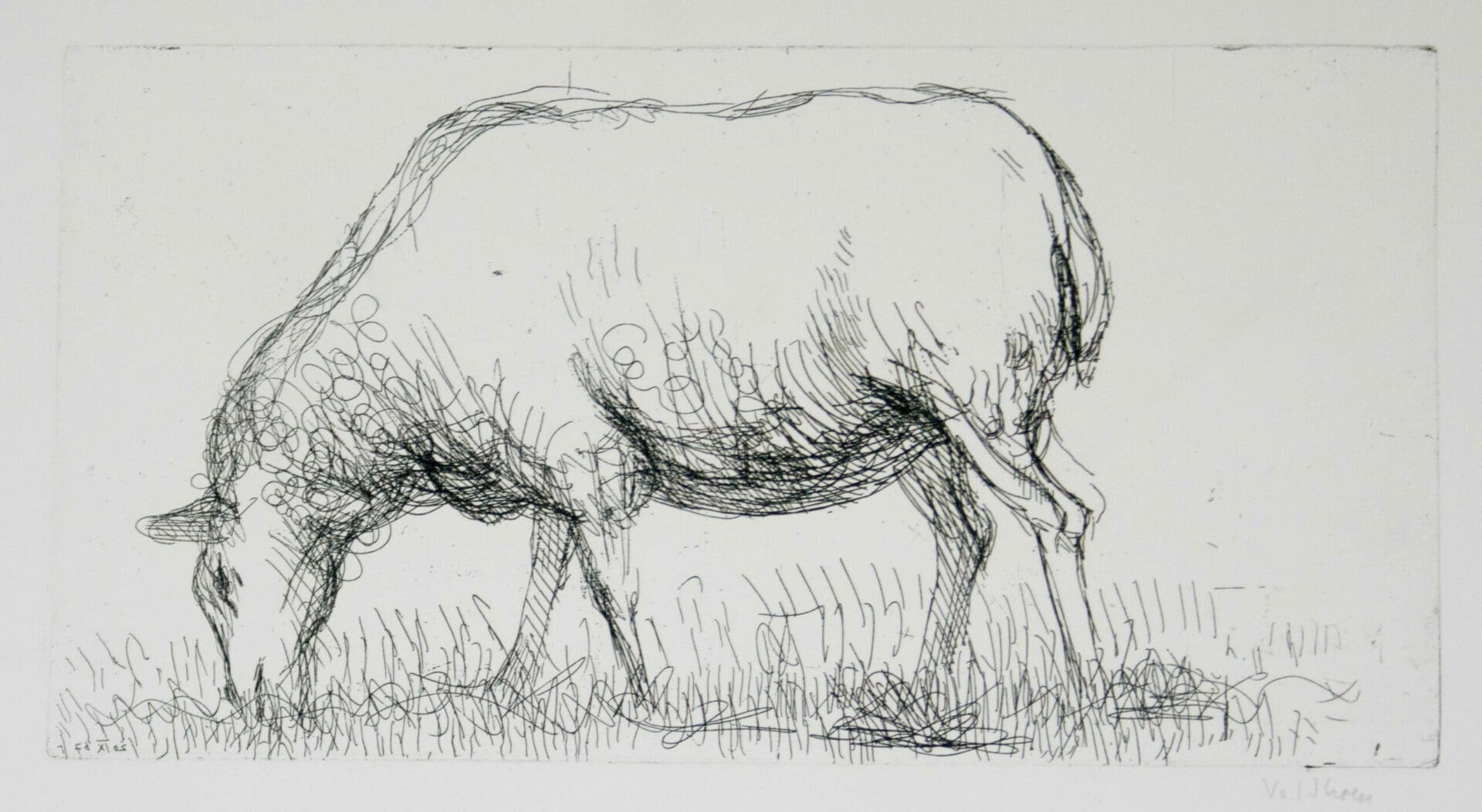

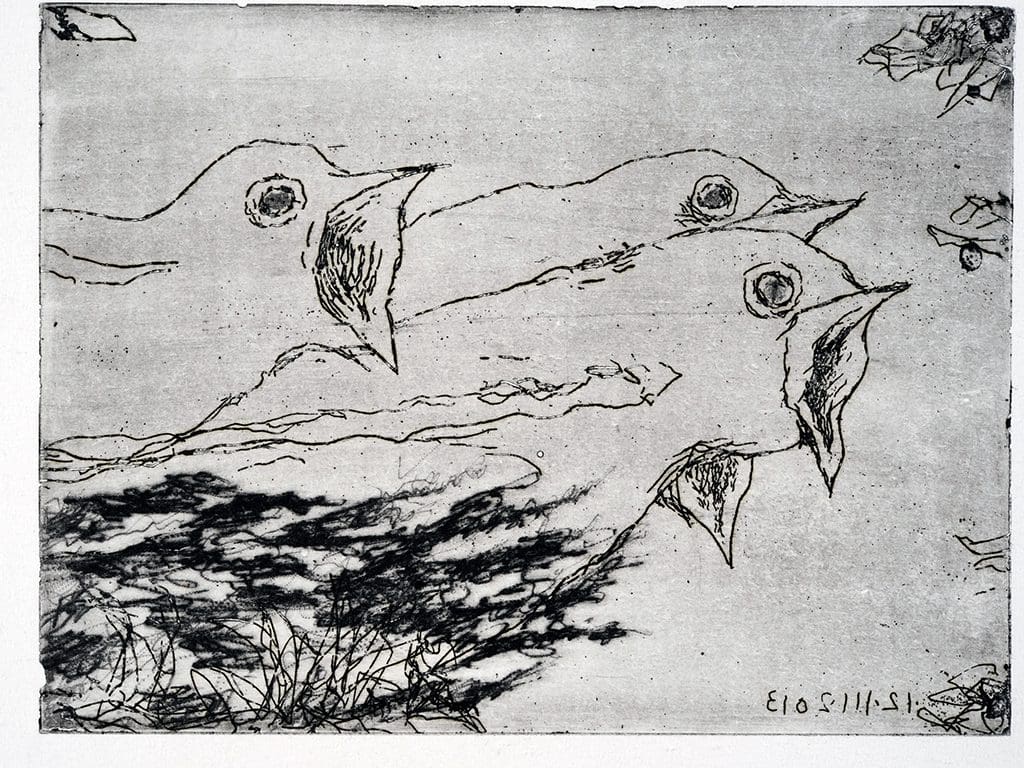

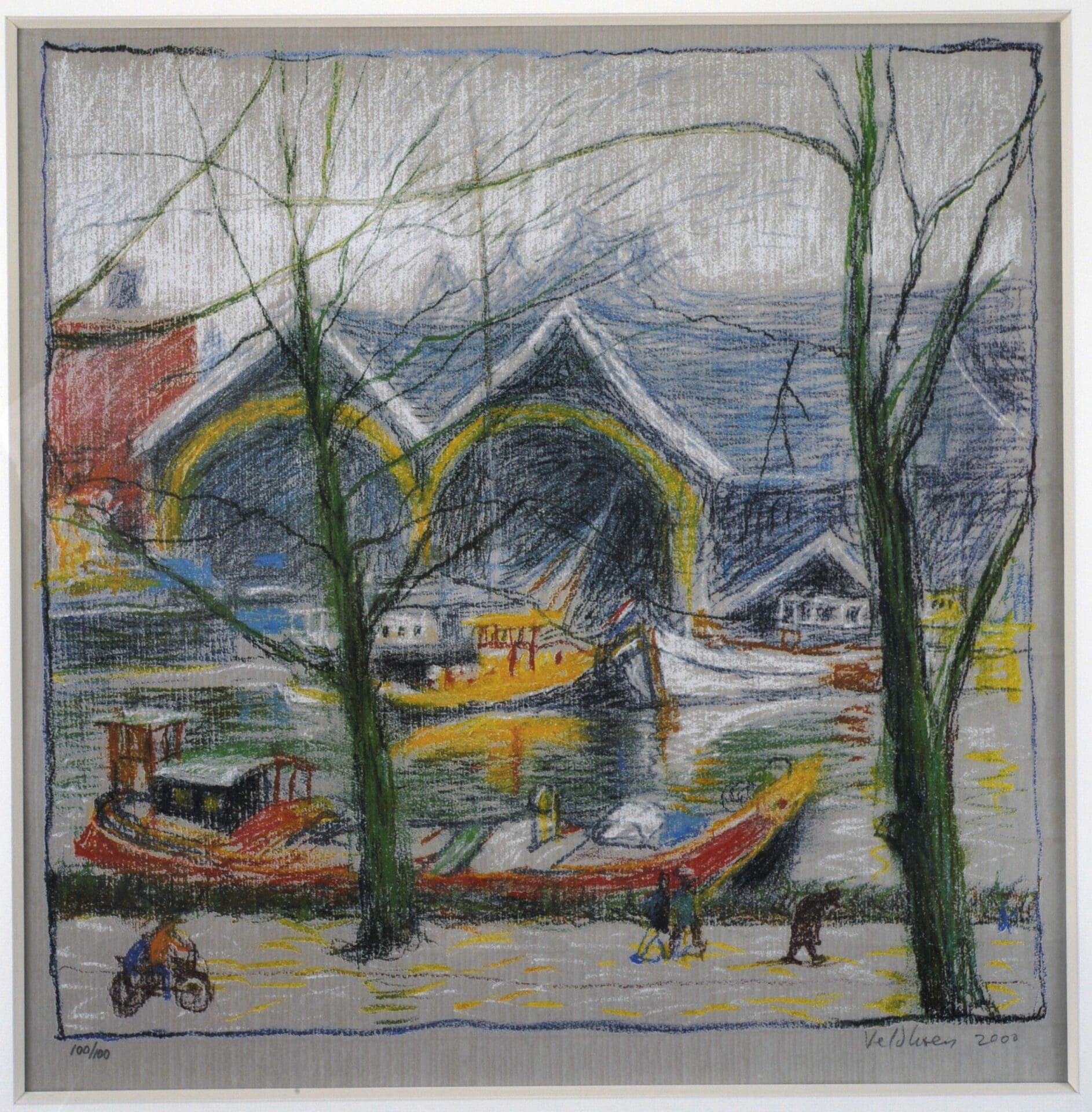

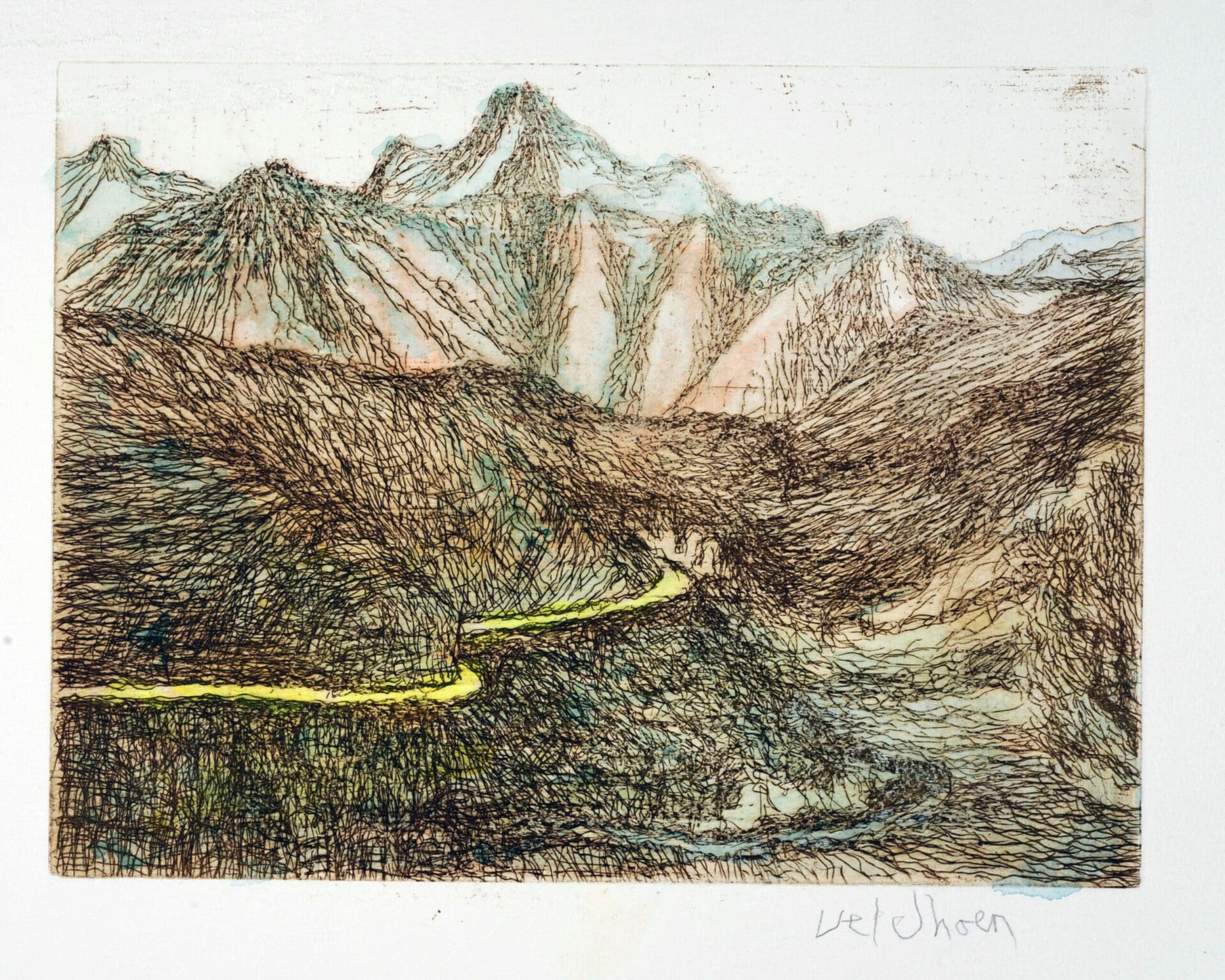

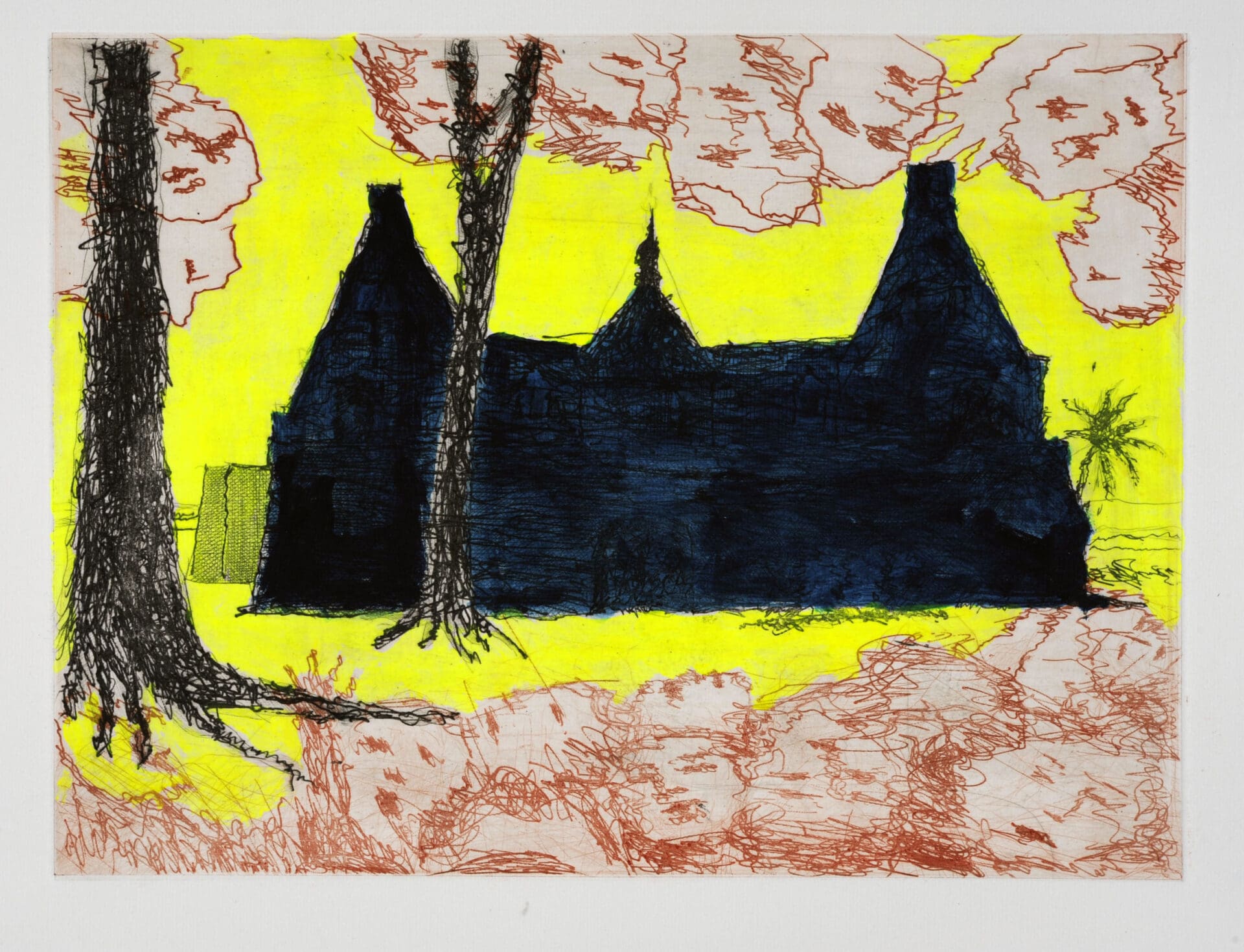

His earliest works include the landscapes that were created in 1956 in the vicinity of Bergen and Schoorl. These often have a desolate atmosphere that arises from Veldhoen’s fascination with the contrast between abandoned bunkers and industrial complexes on the one hand and nature on the other.

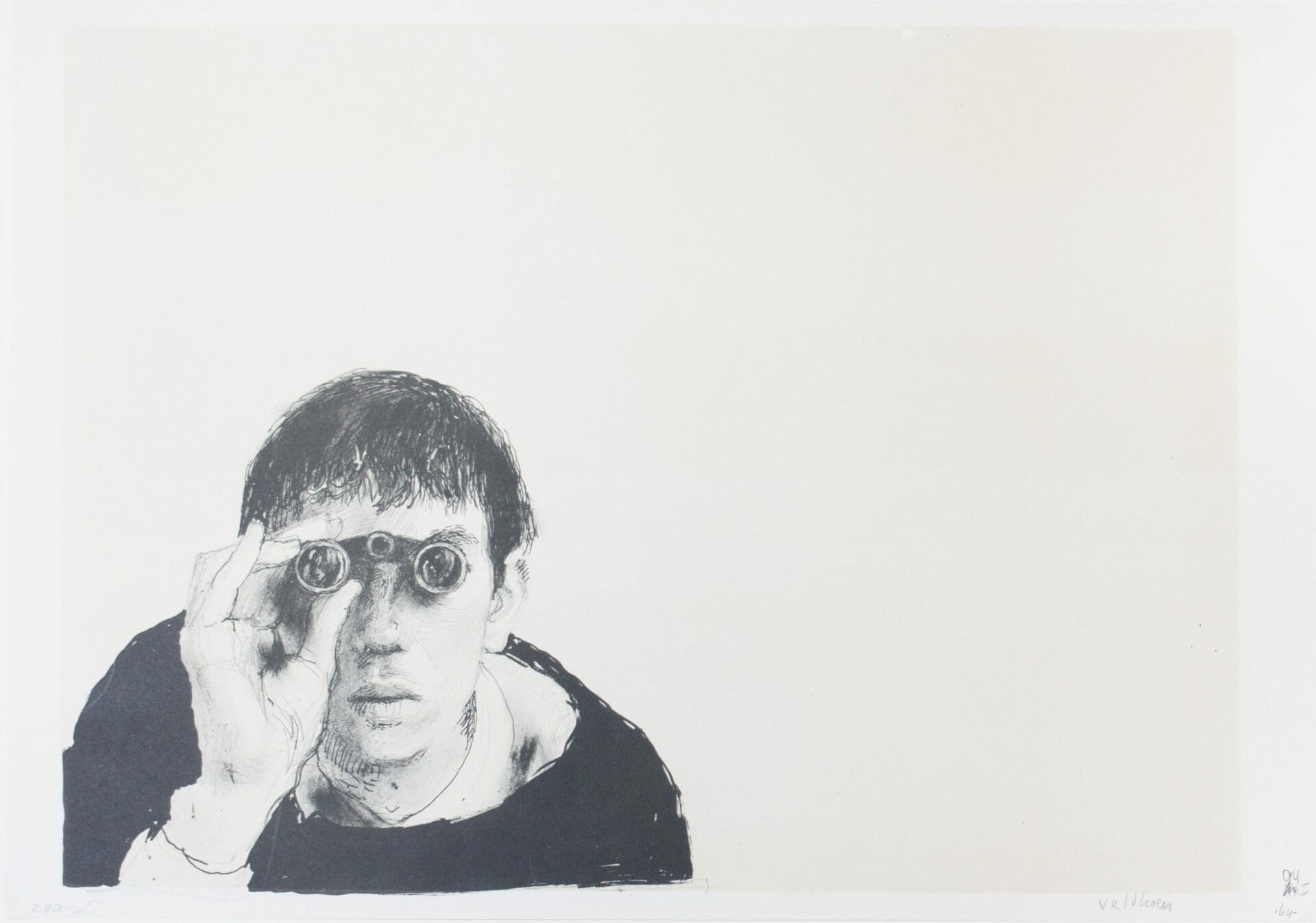

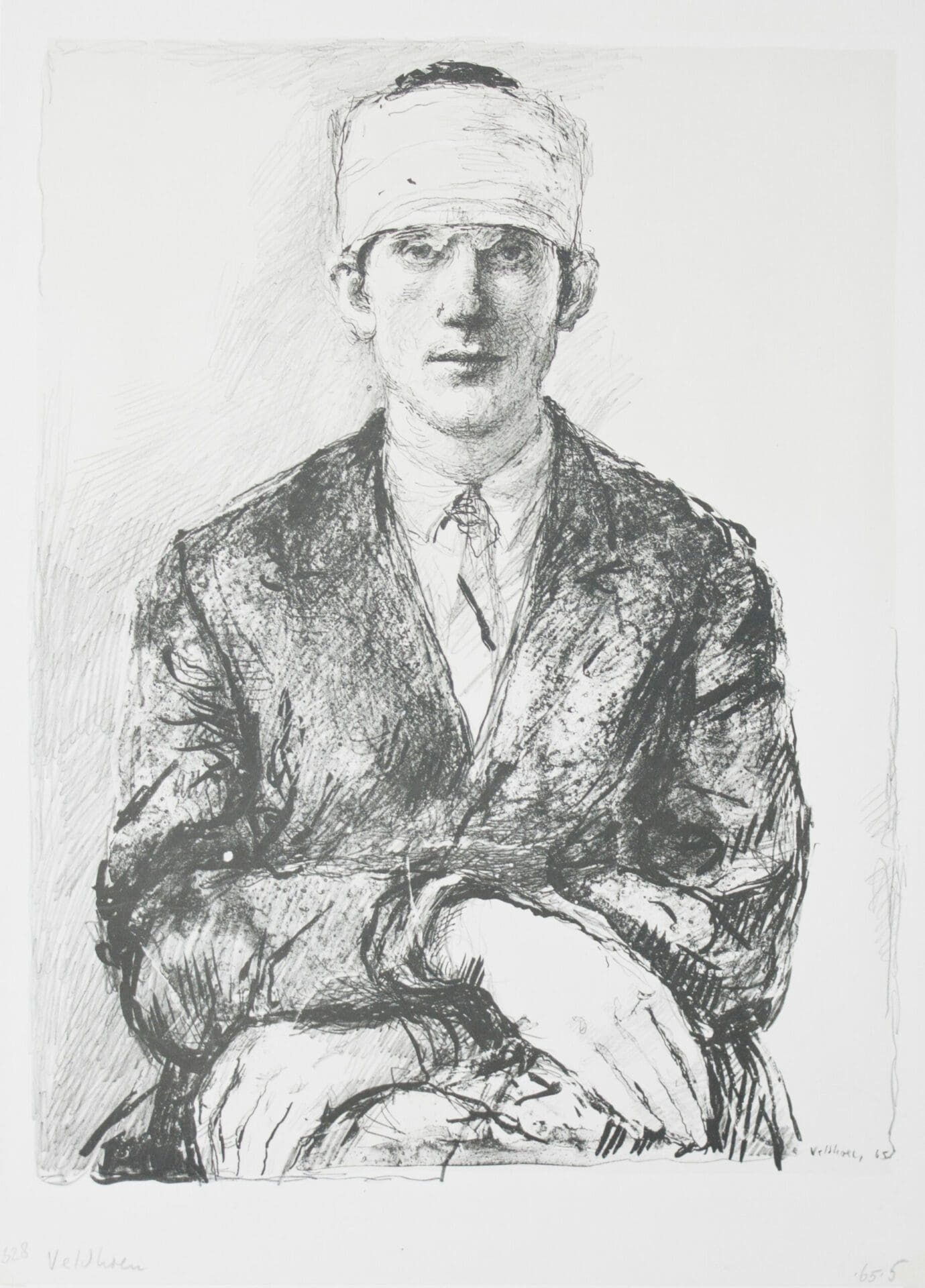

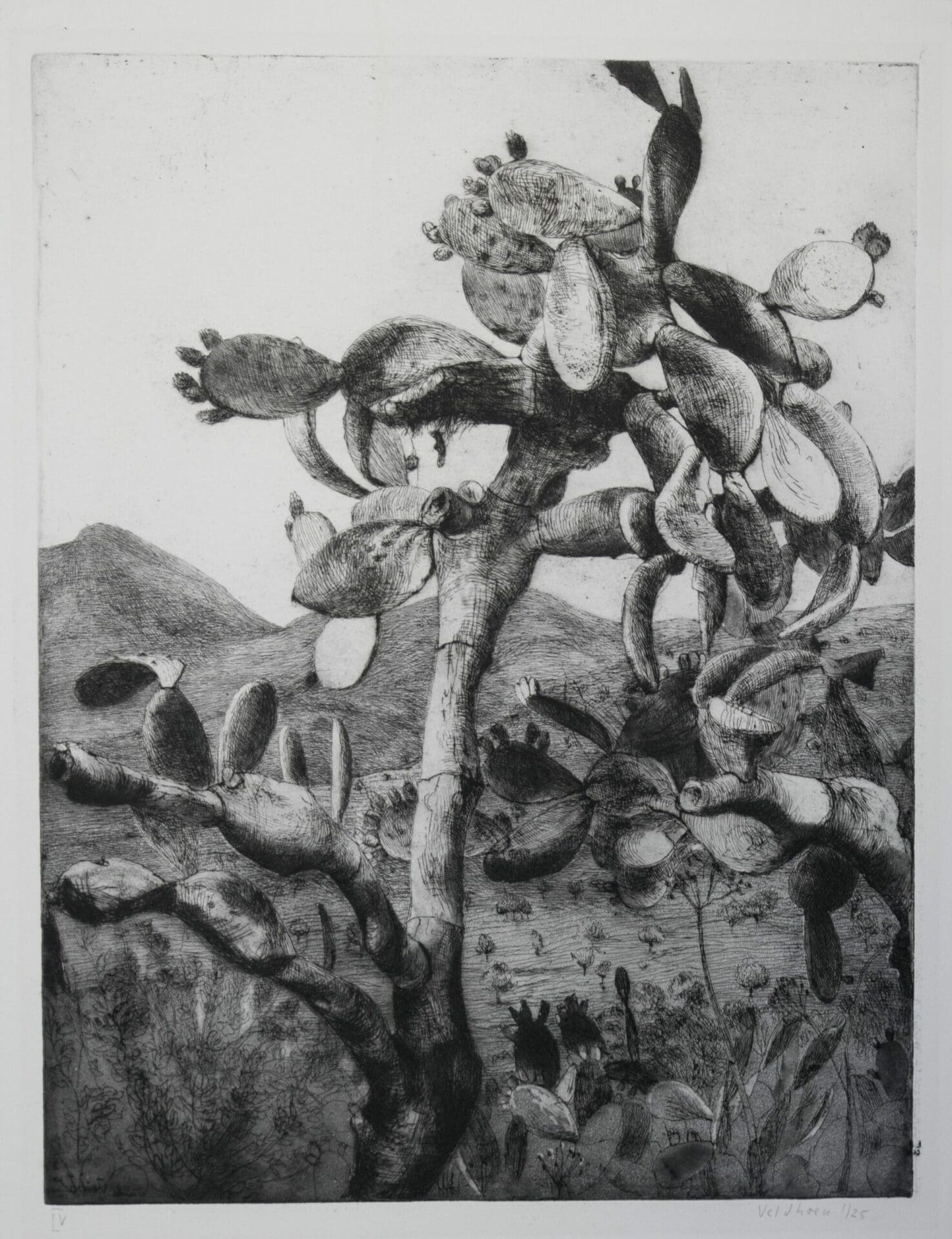

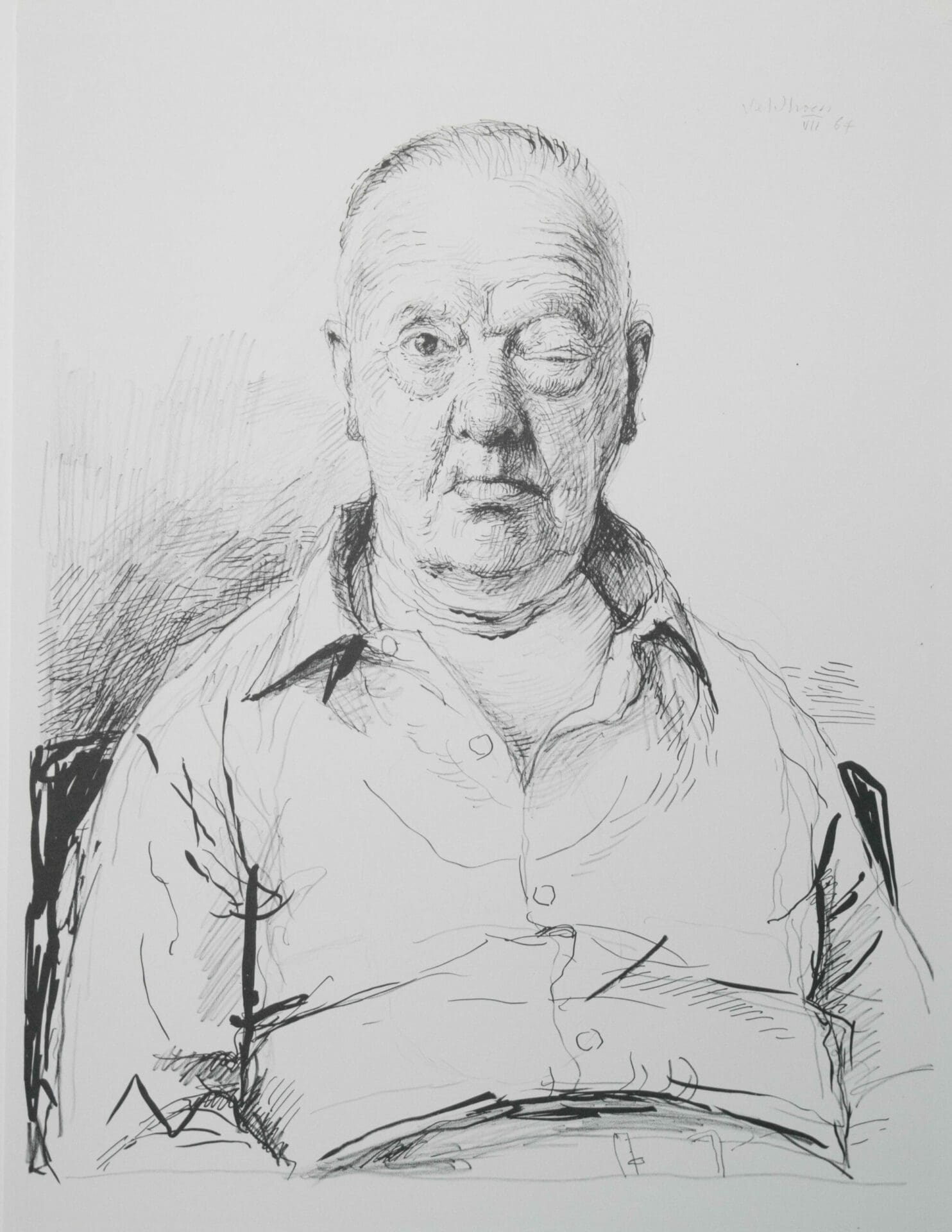

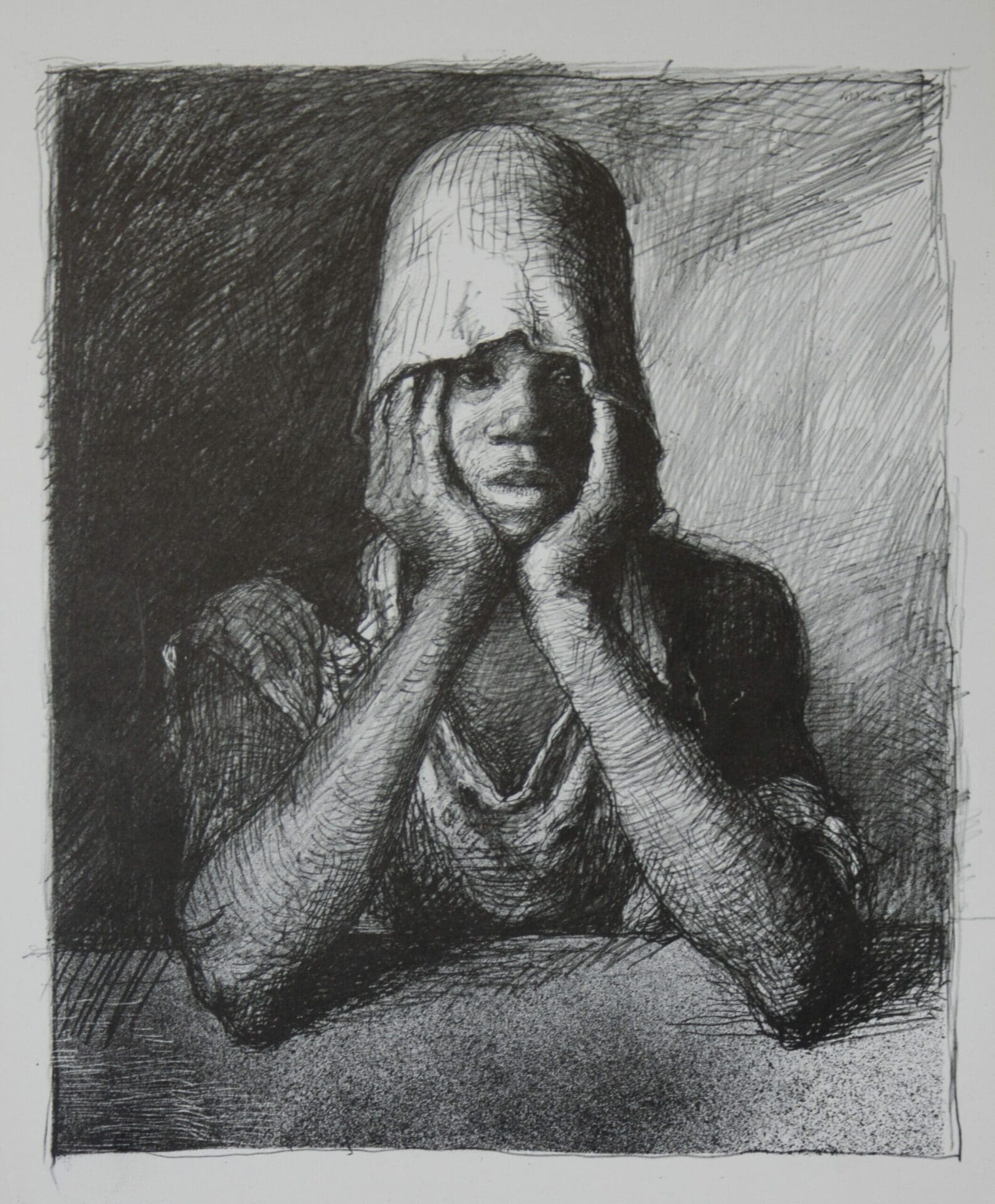

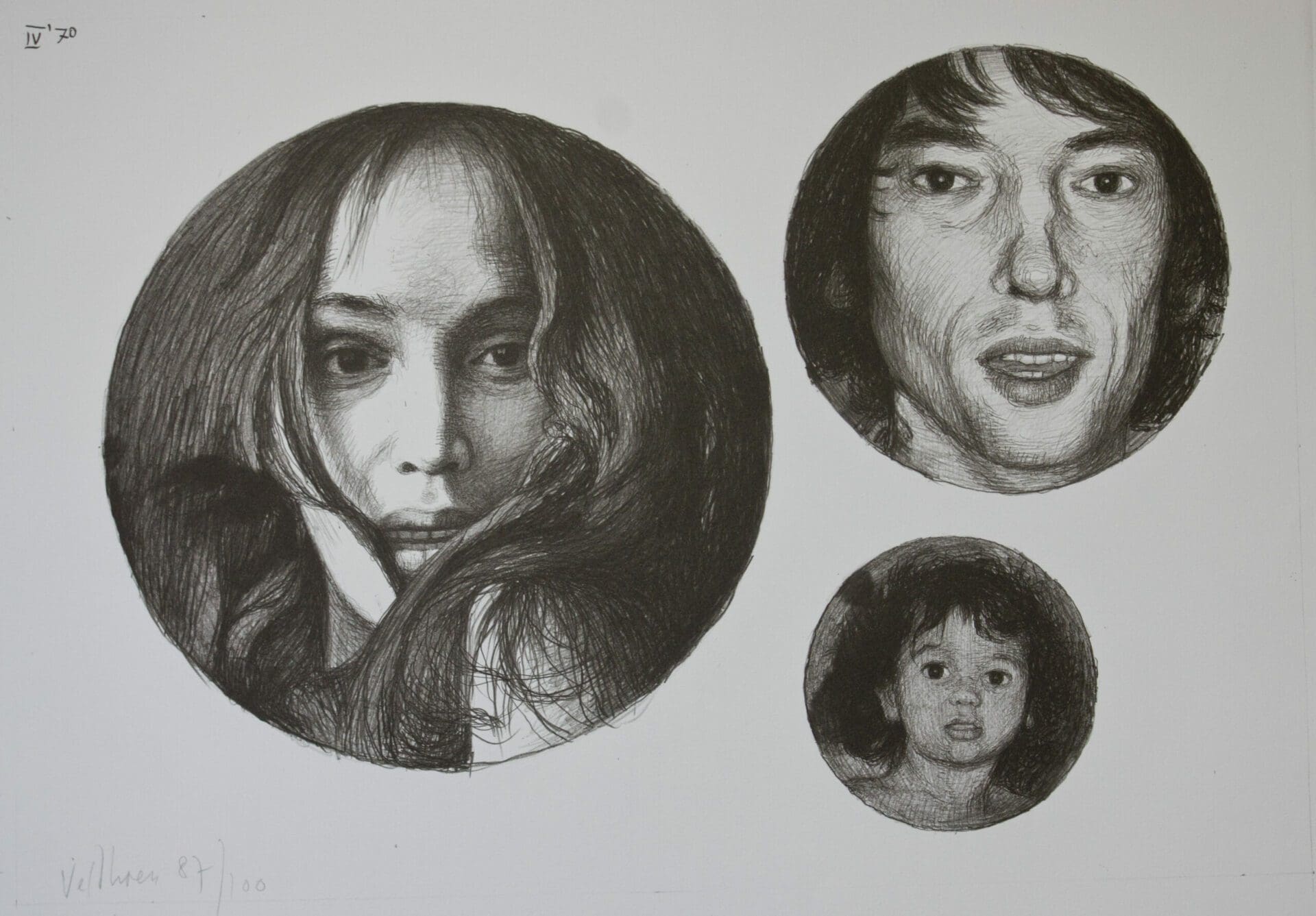

Veldhoen was an artist who loved to travel. Early in his career he visited Ibiza, Spain and Africa, among others. In 1961 he received a travel grant from the Ministry of Education, Arts and Sciences that enabled him to visit Israel. On his travels, Veldhoen not only produced landscapes, but also portraits of indigenous men and women who crossed his path. He also found colourful models in Amsterdam that fascinated him.

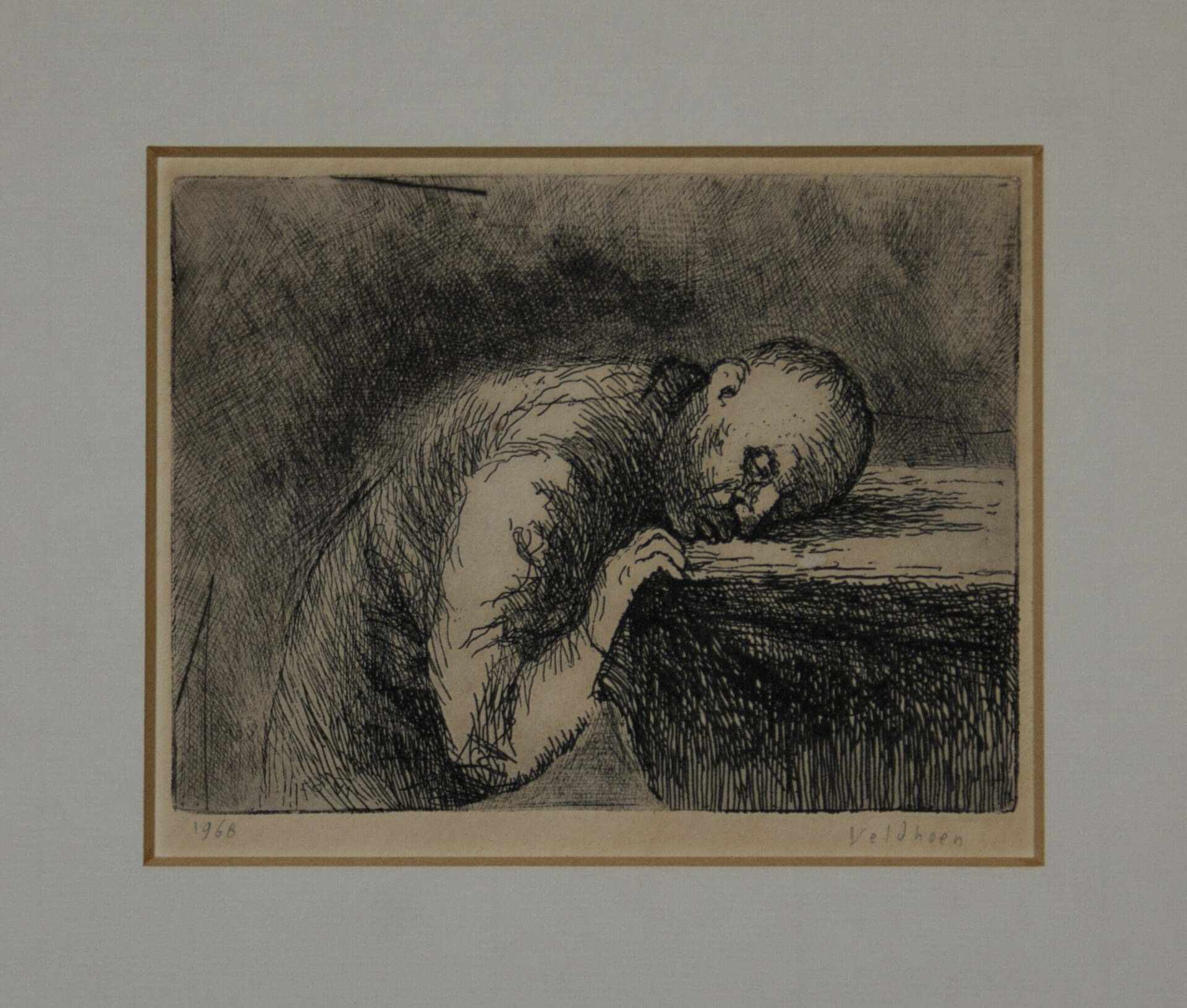

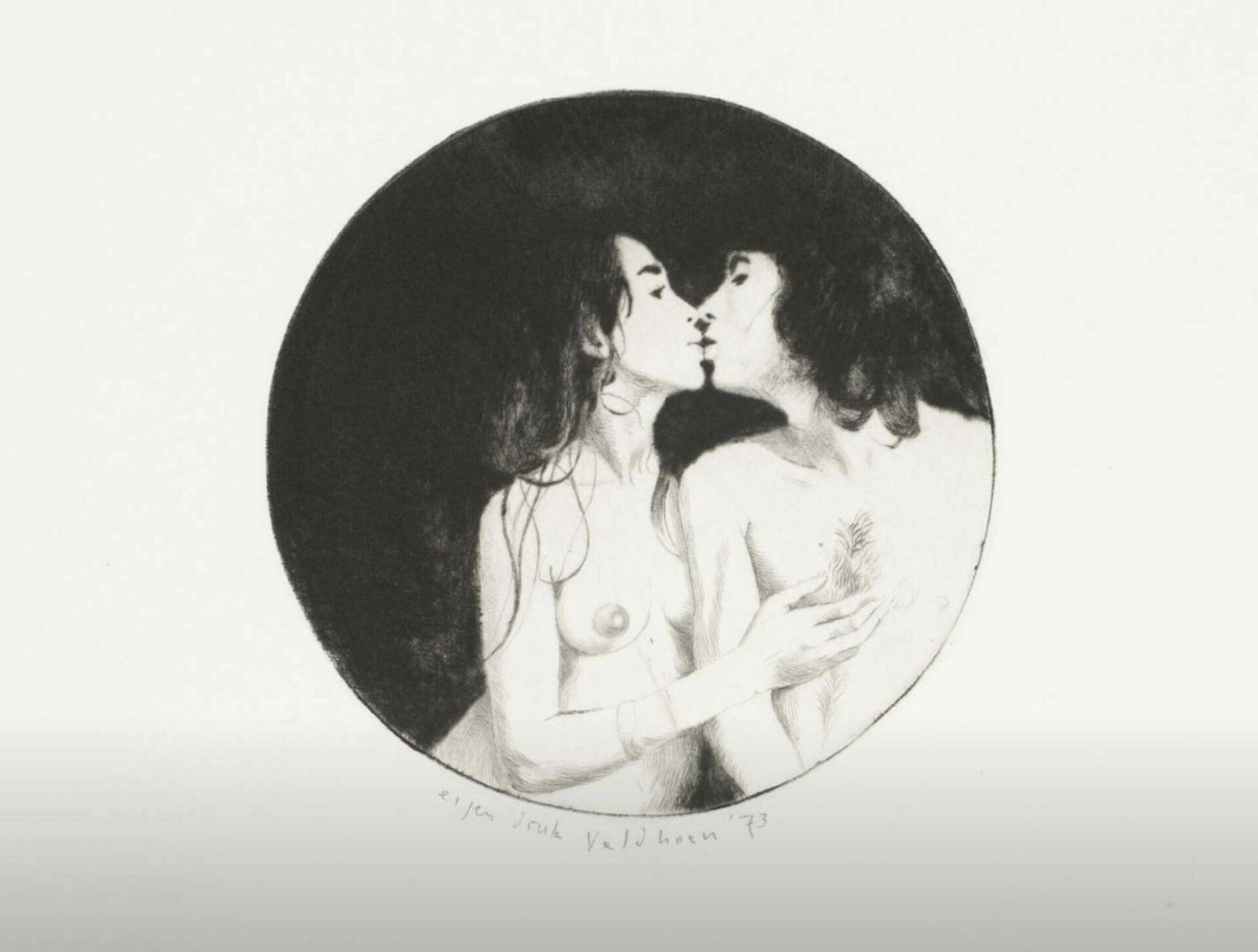

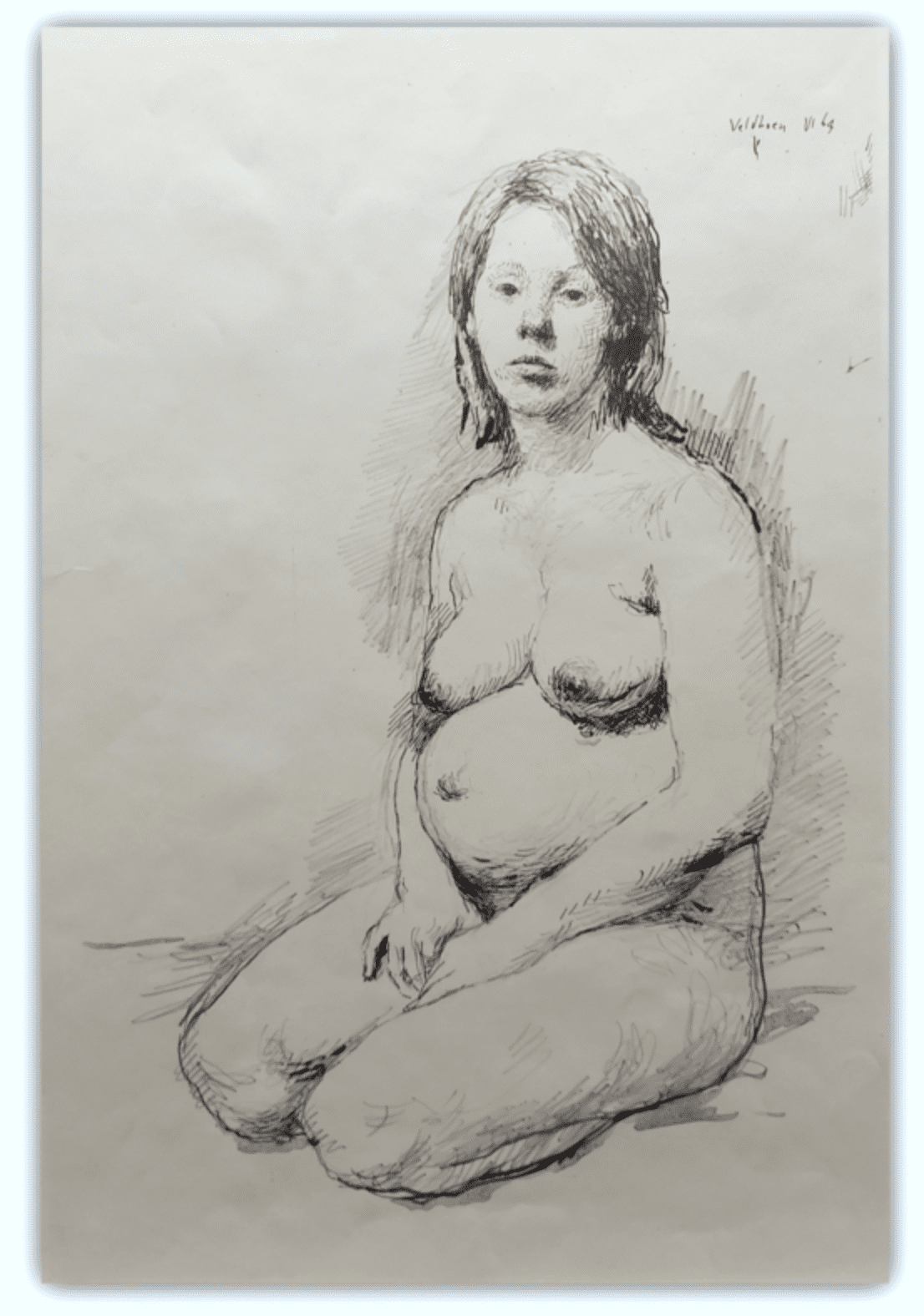

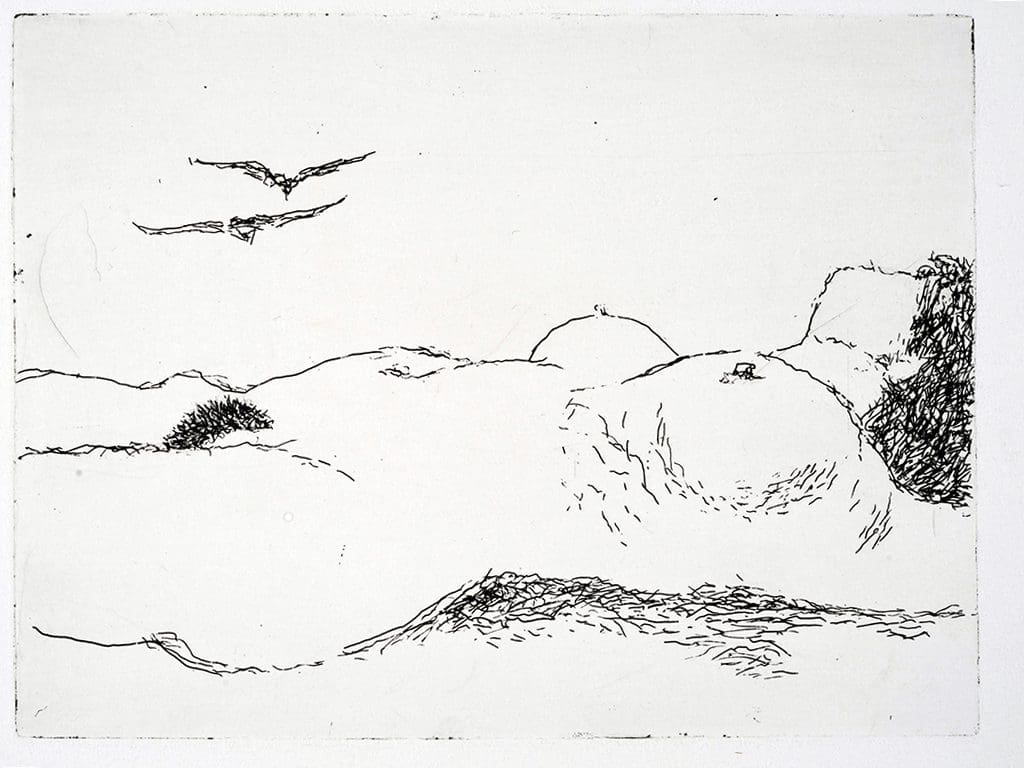

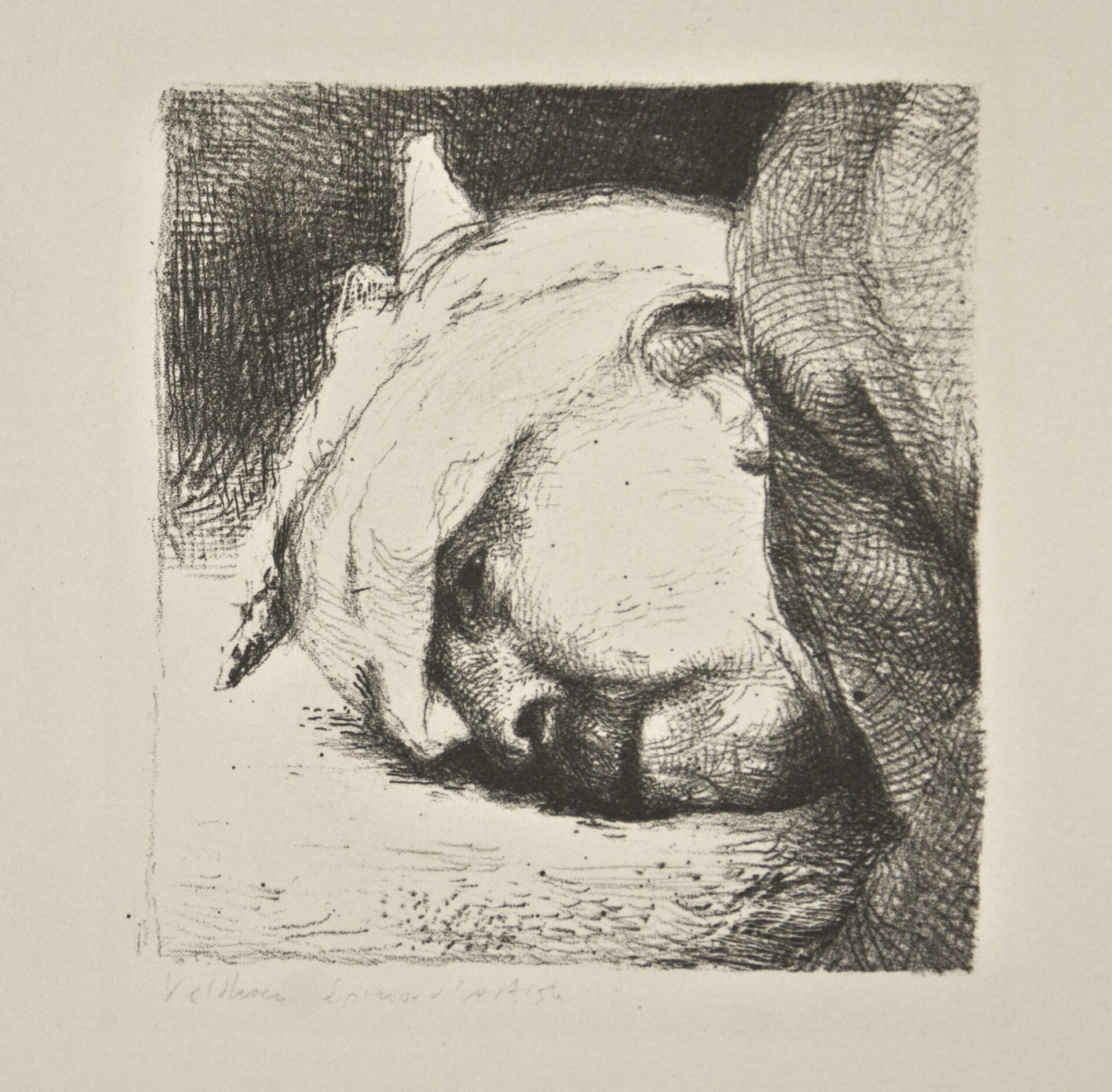

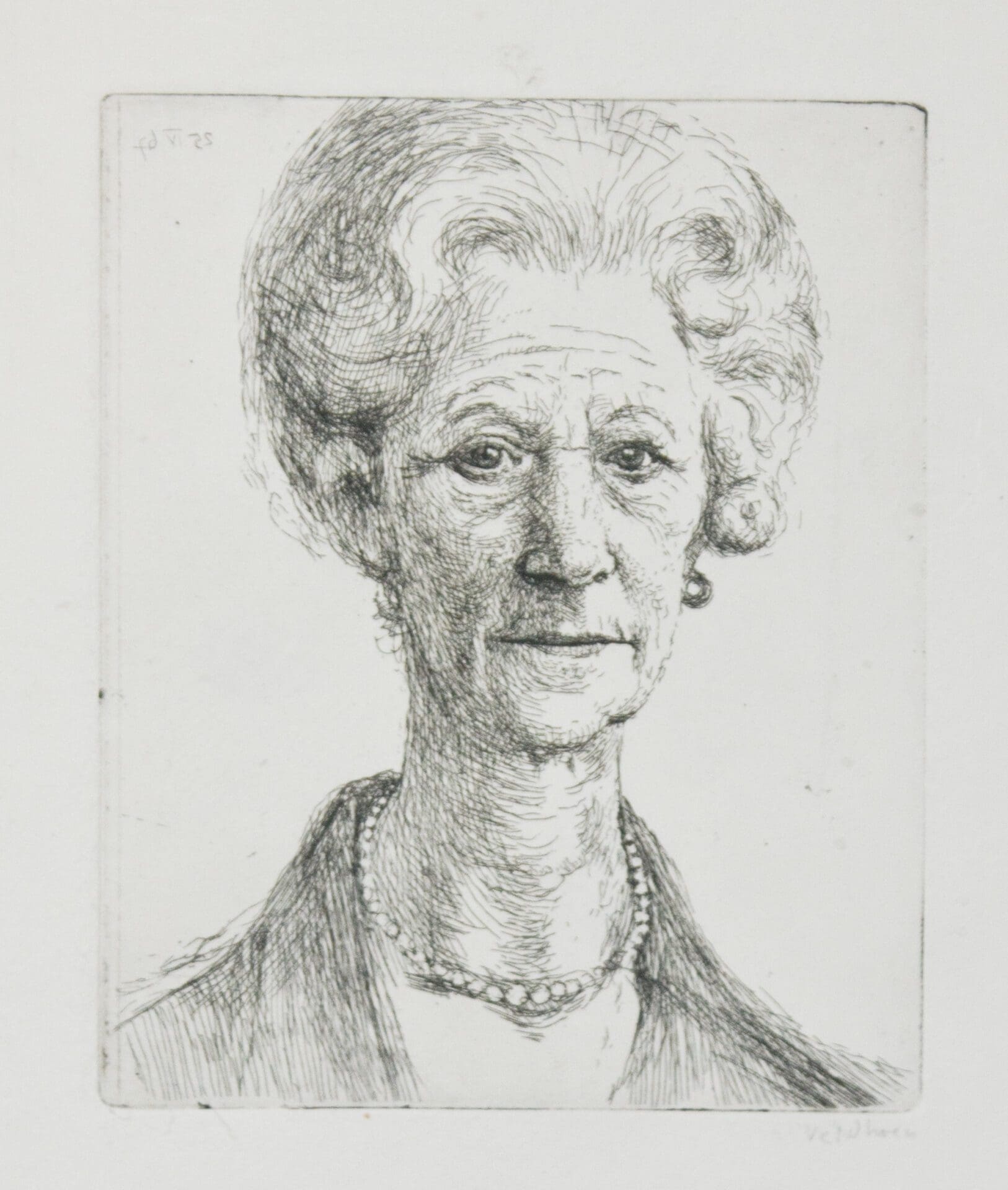

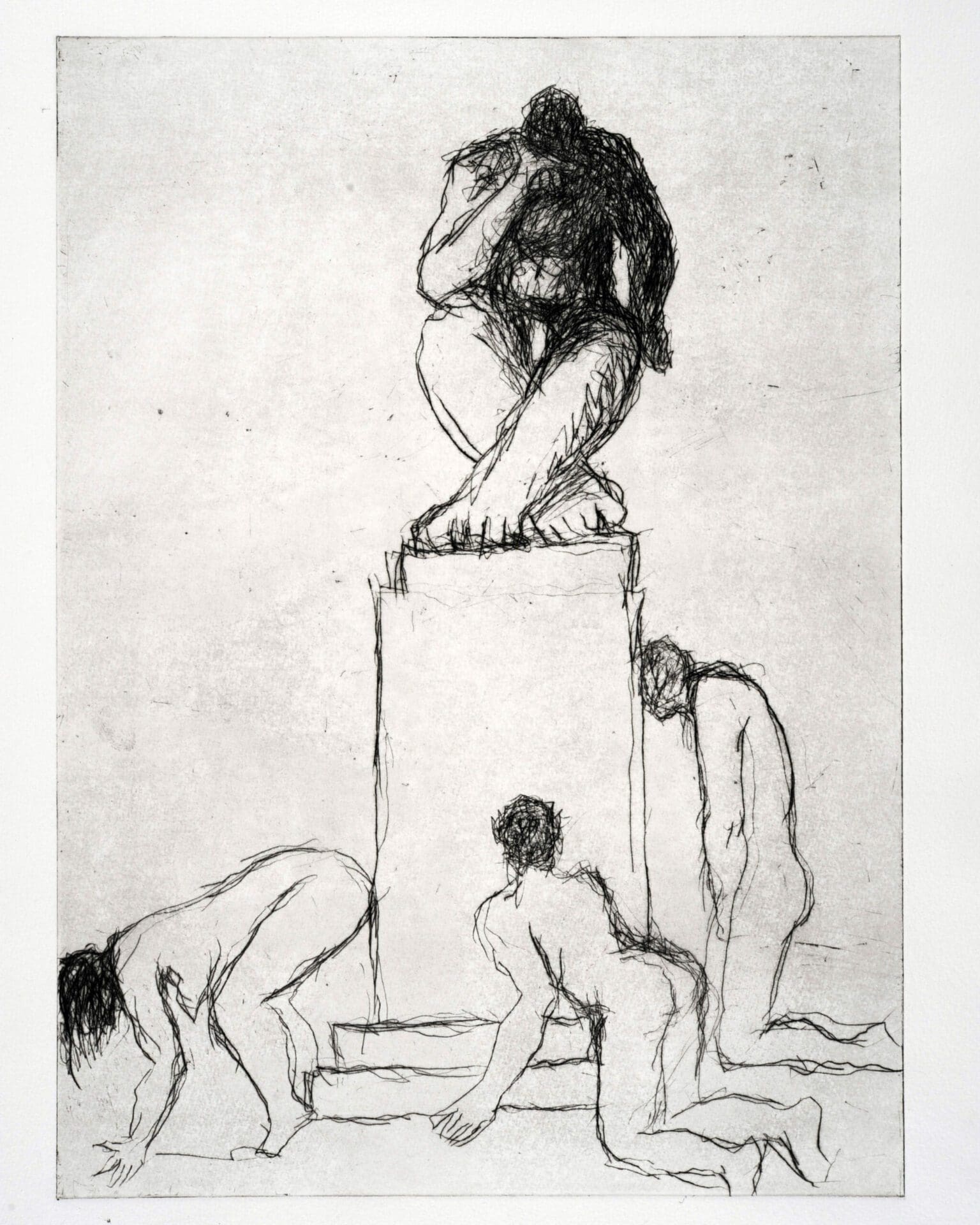

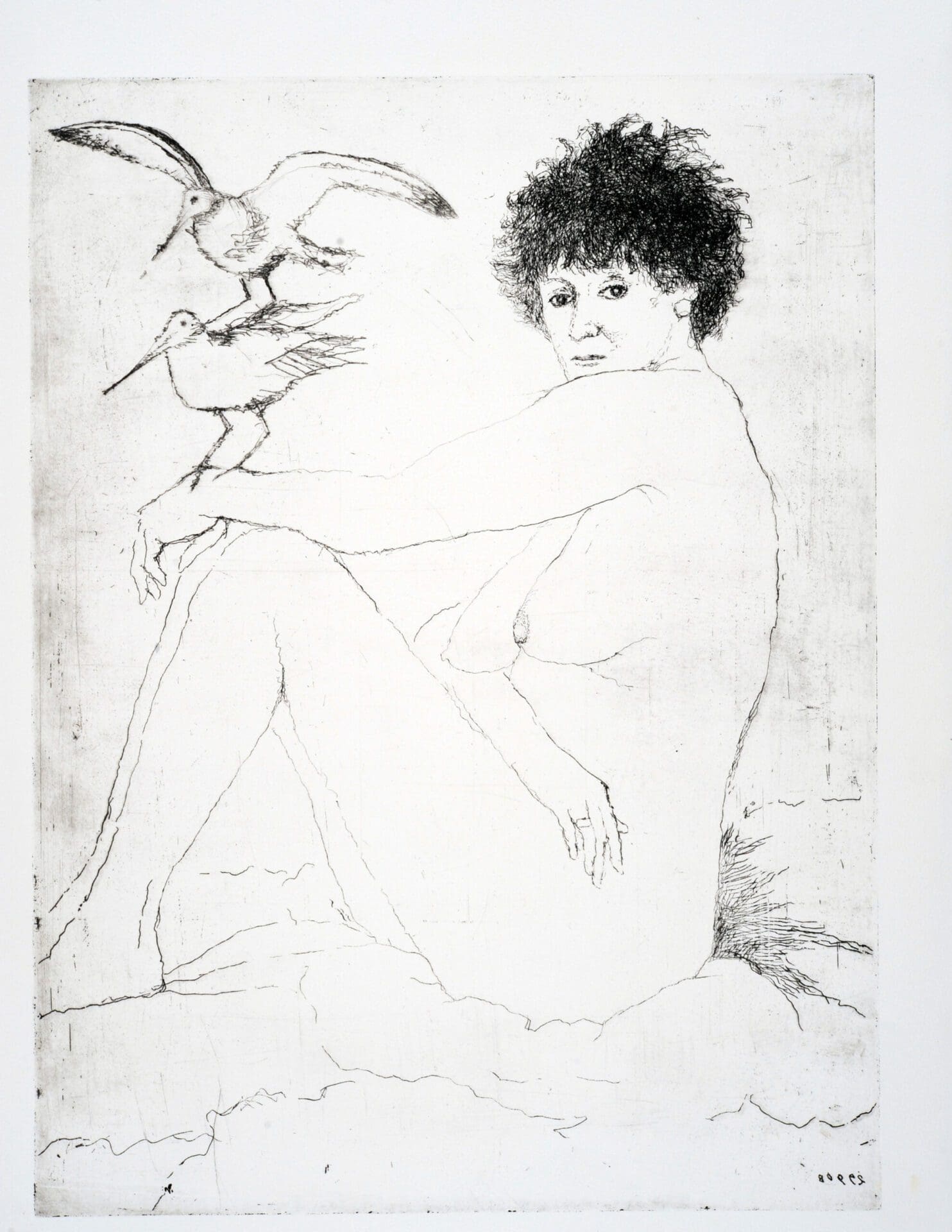

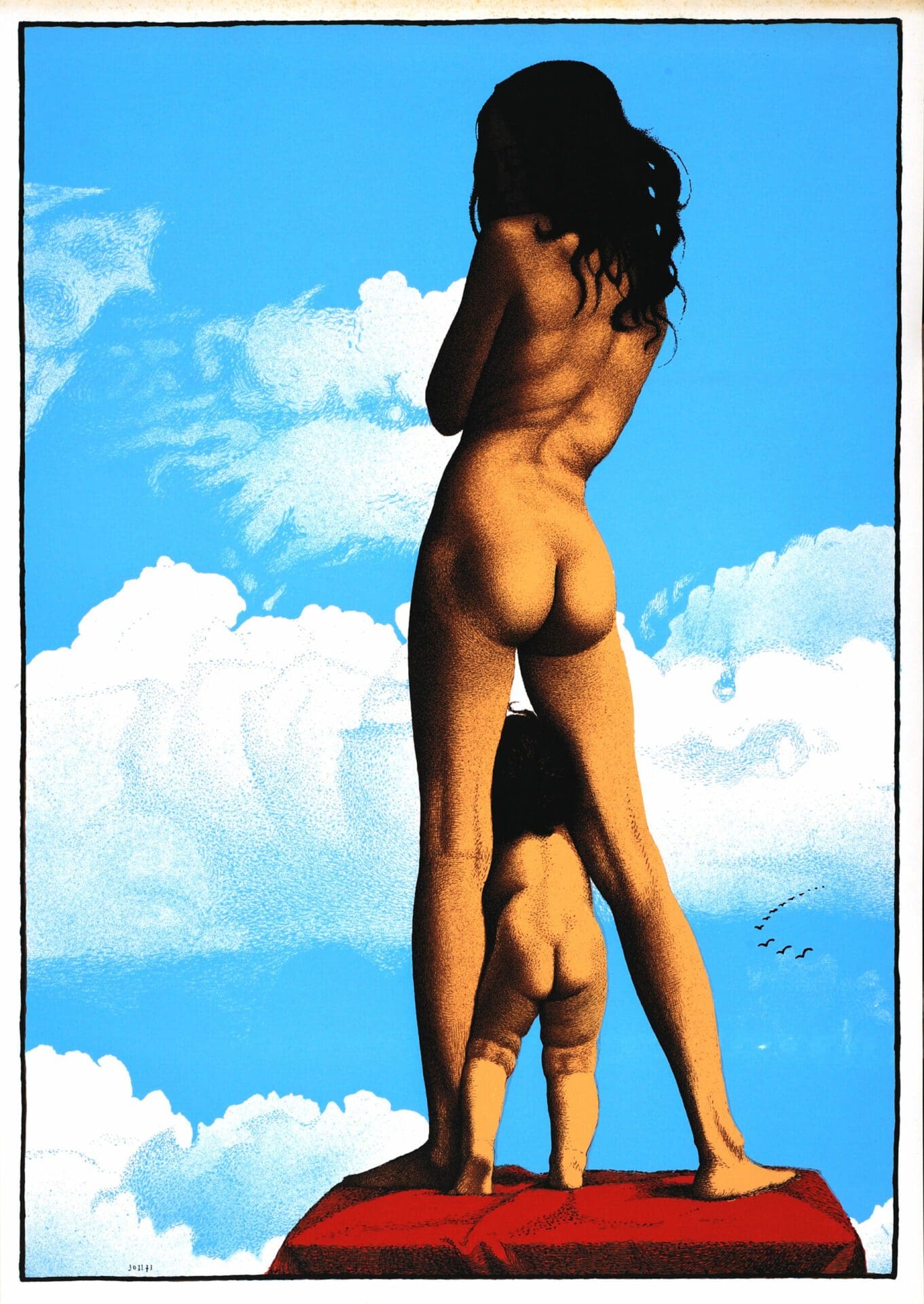

If there is one subject to which Veldhoen remained faithful throughout his career as an etcher, it is the female nude. In addition to many anonymous models, Veldhoen mainly portrayed friends and acquaintances. The women who posed naked for him were, almost without exception, from his immediate environment. His earliest portraits have a certain abstraction, but as time progressed his portraits became more and more realistic. According to Veldhoen, the stylization of the early work arose from his unfamiliarity with the etching technique.

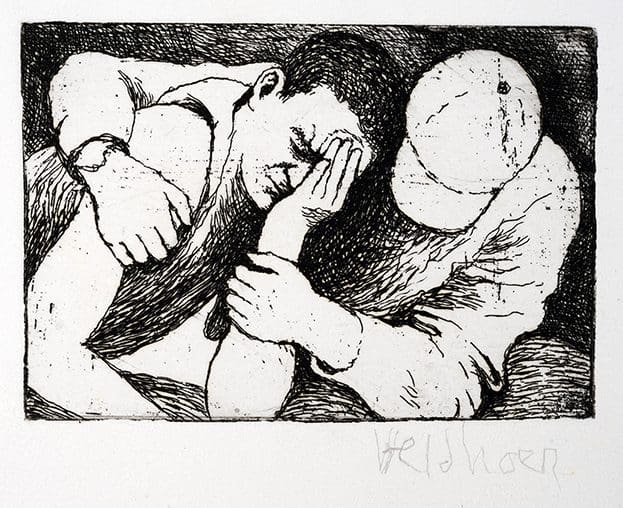

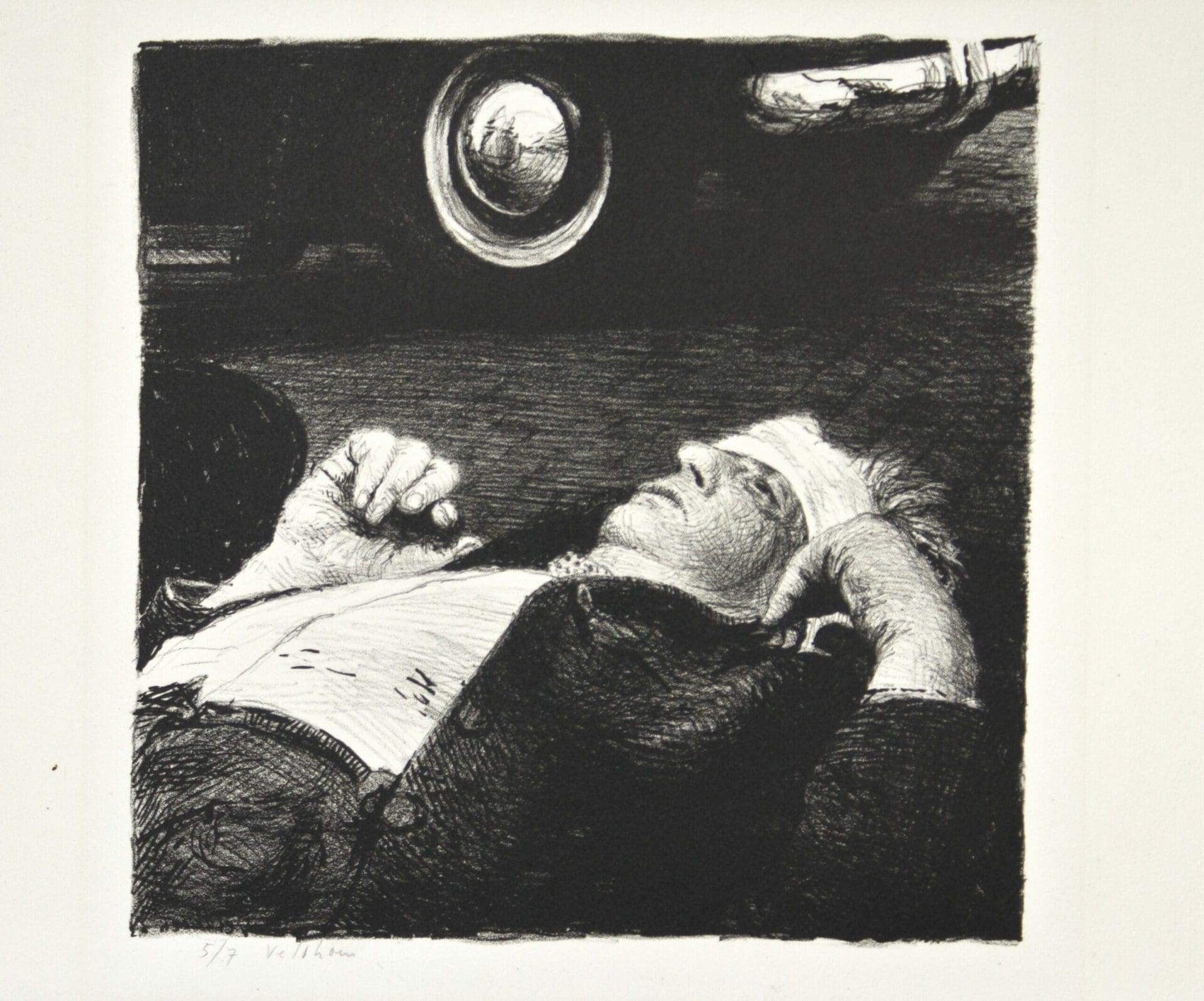

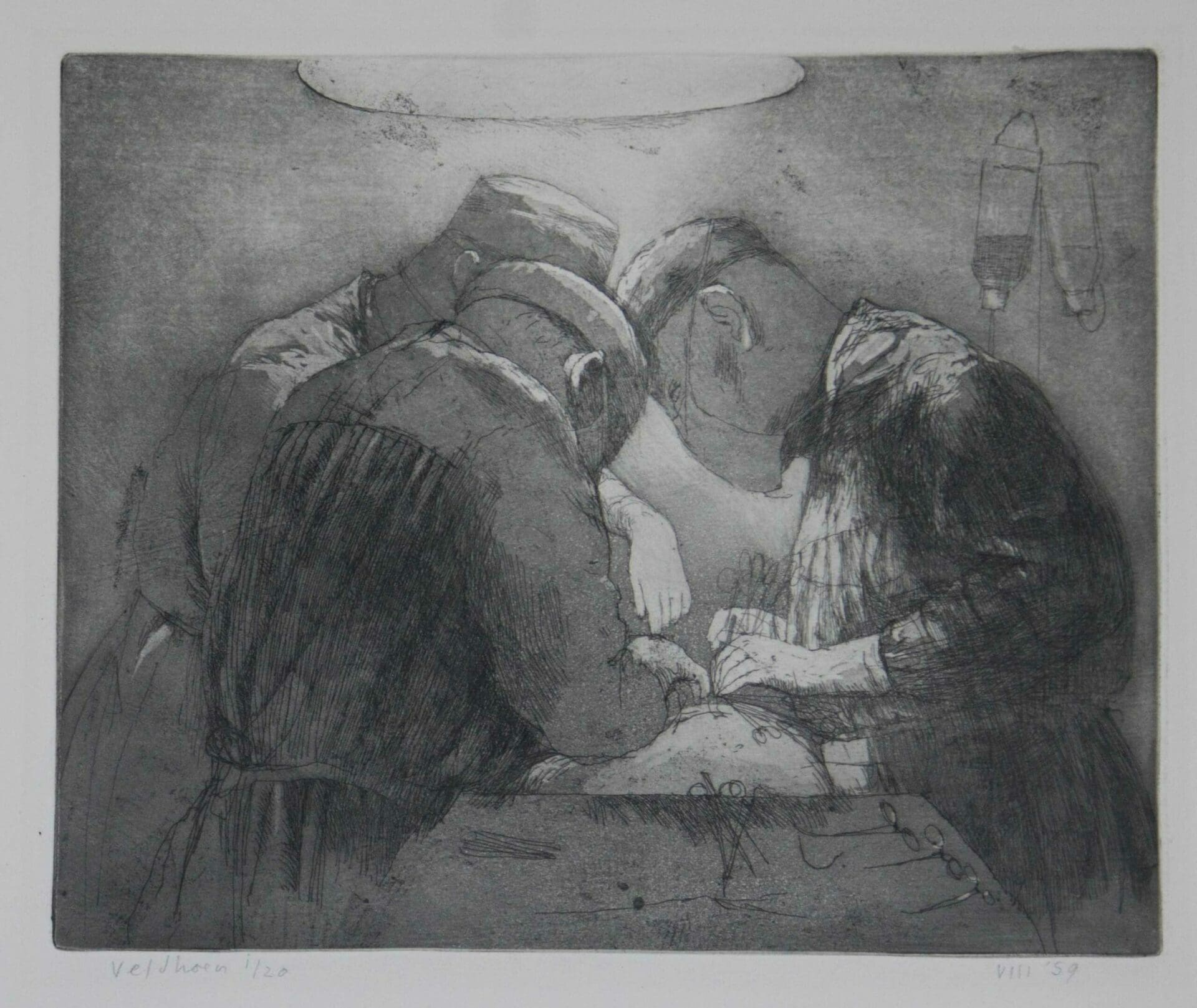

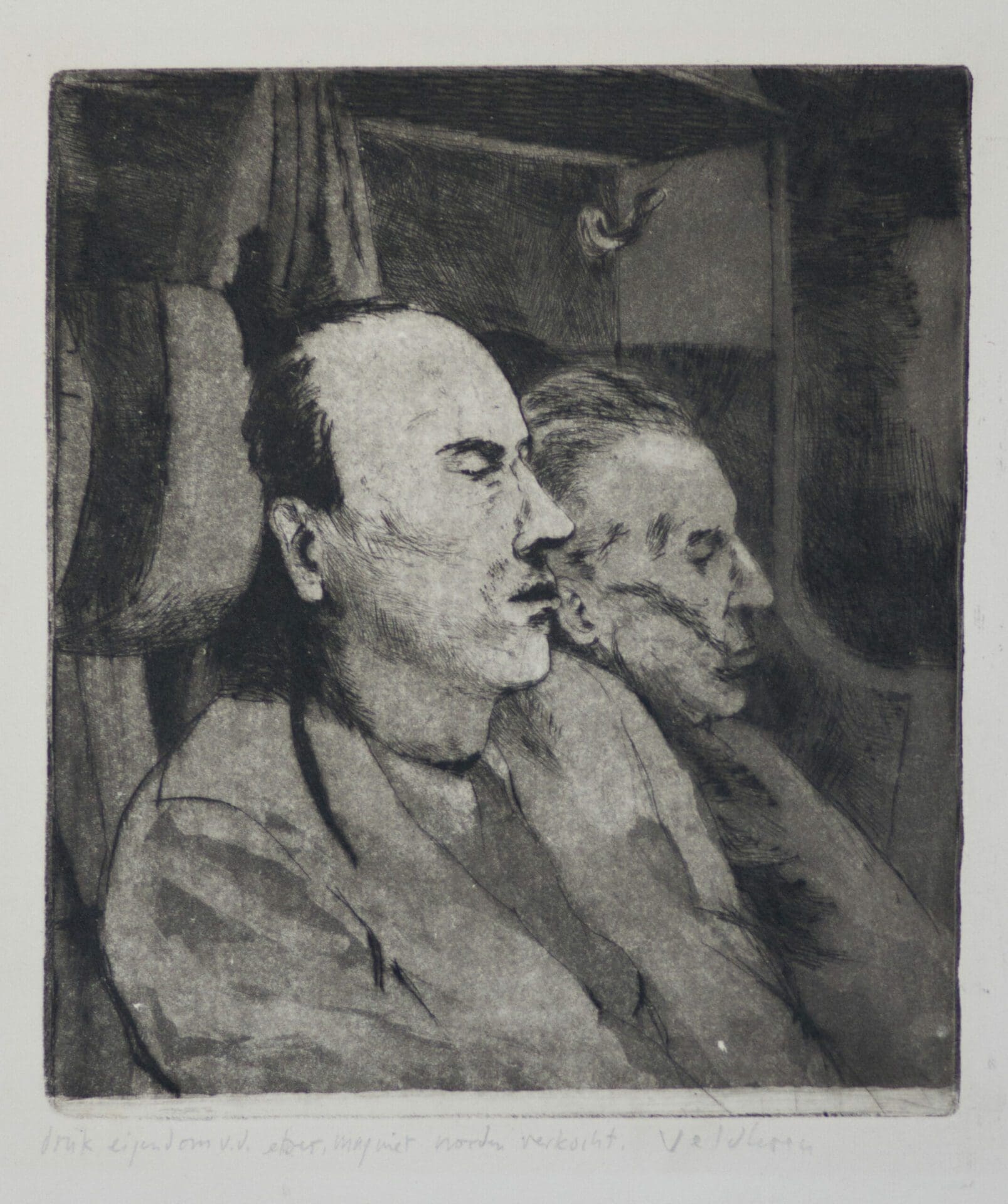

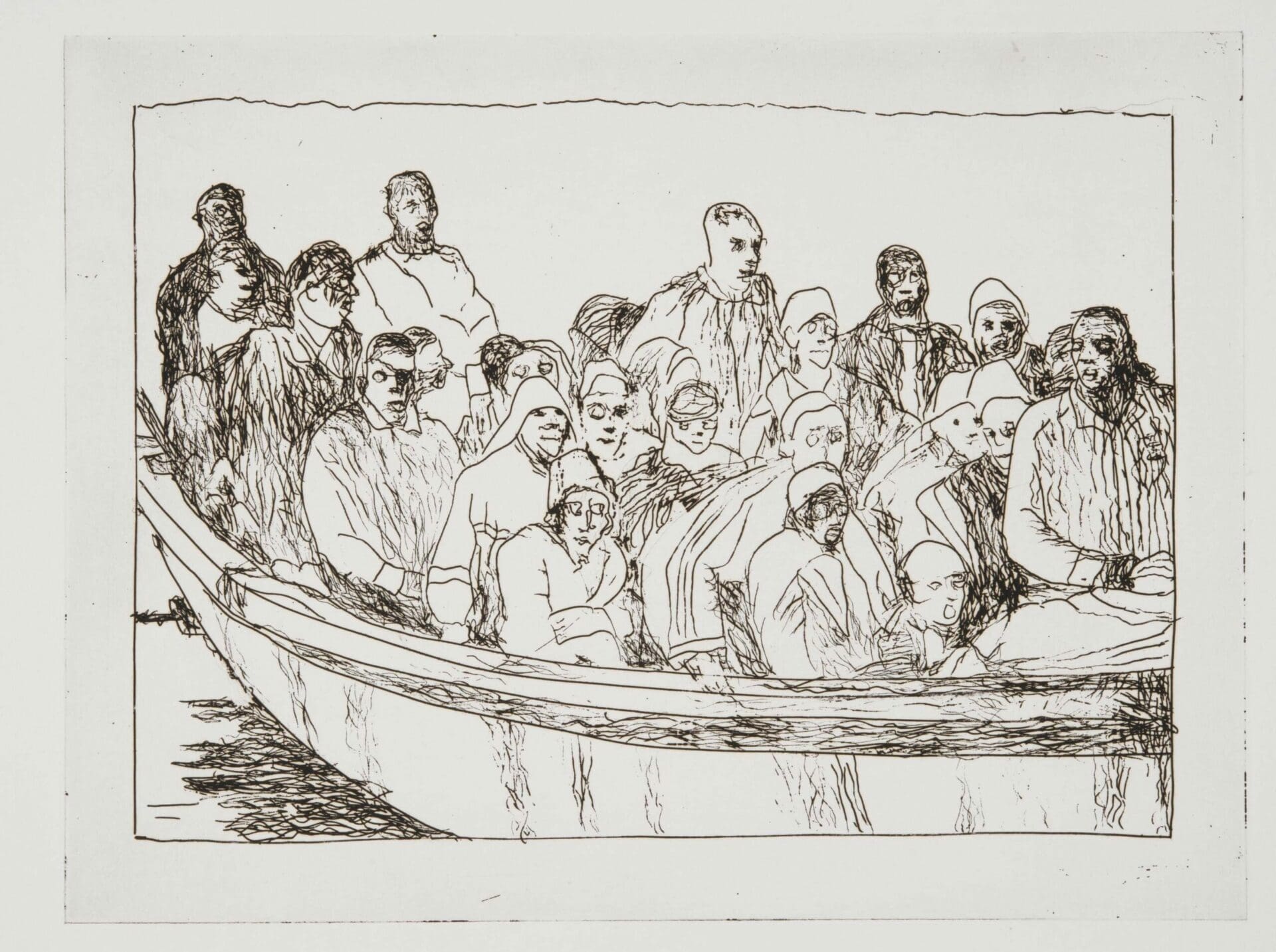

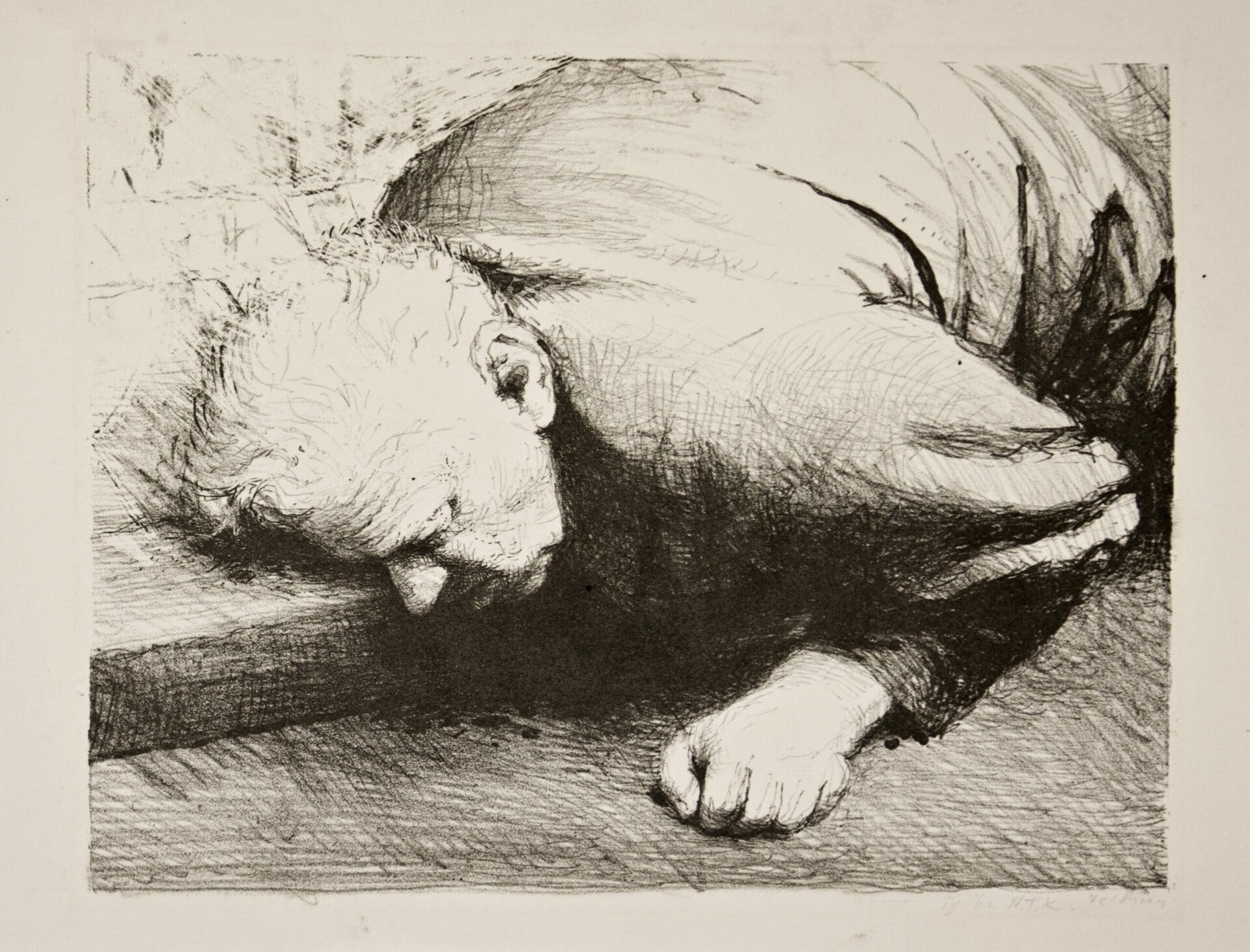

A special place within his oeuvre is occupied by the series with couples making love. The impetus for this also came from the work of Rembrandt, who created two explicit lovemaking scenes. Prints like these were completely wrongly labelled by moral crusaders as “stimulating the senses” and Veldhoen was even convicted in 1964 for making pornographic material. If there is one thing these prints lack, it is the complete absence of vulgar voyeurism. Veldhoen is nothing of a peeping tom. On the contrary, he succeeds time and again in an inimitable way to evoke feelings of intimacy and vulnerability in the viewer. The feeling of compassion that is so characteristic of his art is expressed very emphatically in the series of prints dedicated to women in labour and victims of street accidents. Nowhere else does Veldhoen manage to convey the feeling of loneliness and compassion as oppressively and compellingly as with these prints. According to Veldhoen, printmaking was a social art form, because it is circulation art. By printing multiple copies, the price could remain relatively low. From that perspective, it is not surprising that he welcomed the arrival of the offset rotary press with great enthusiasm. In fact, there was no difference between traditional lithography and the rotary press except that the rotary press could print huge print runs in a short time and the artist no longer had to draw on a heavy stone, but on a light aluminium plate that, once ready, was stretched onto a cylinder.

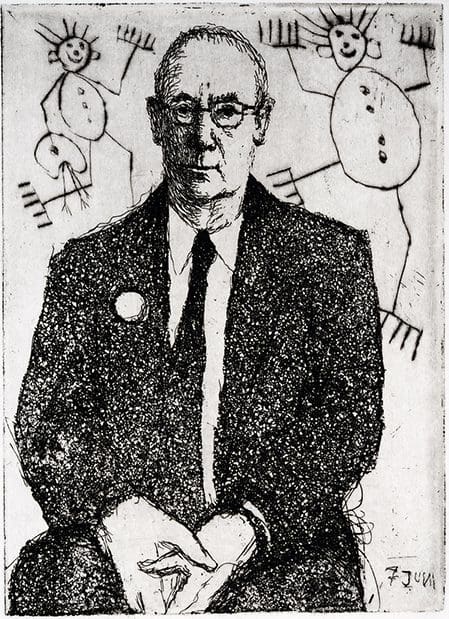

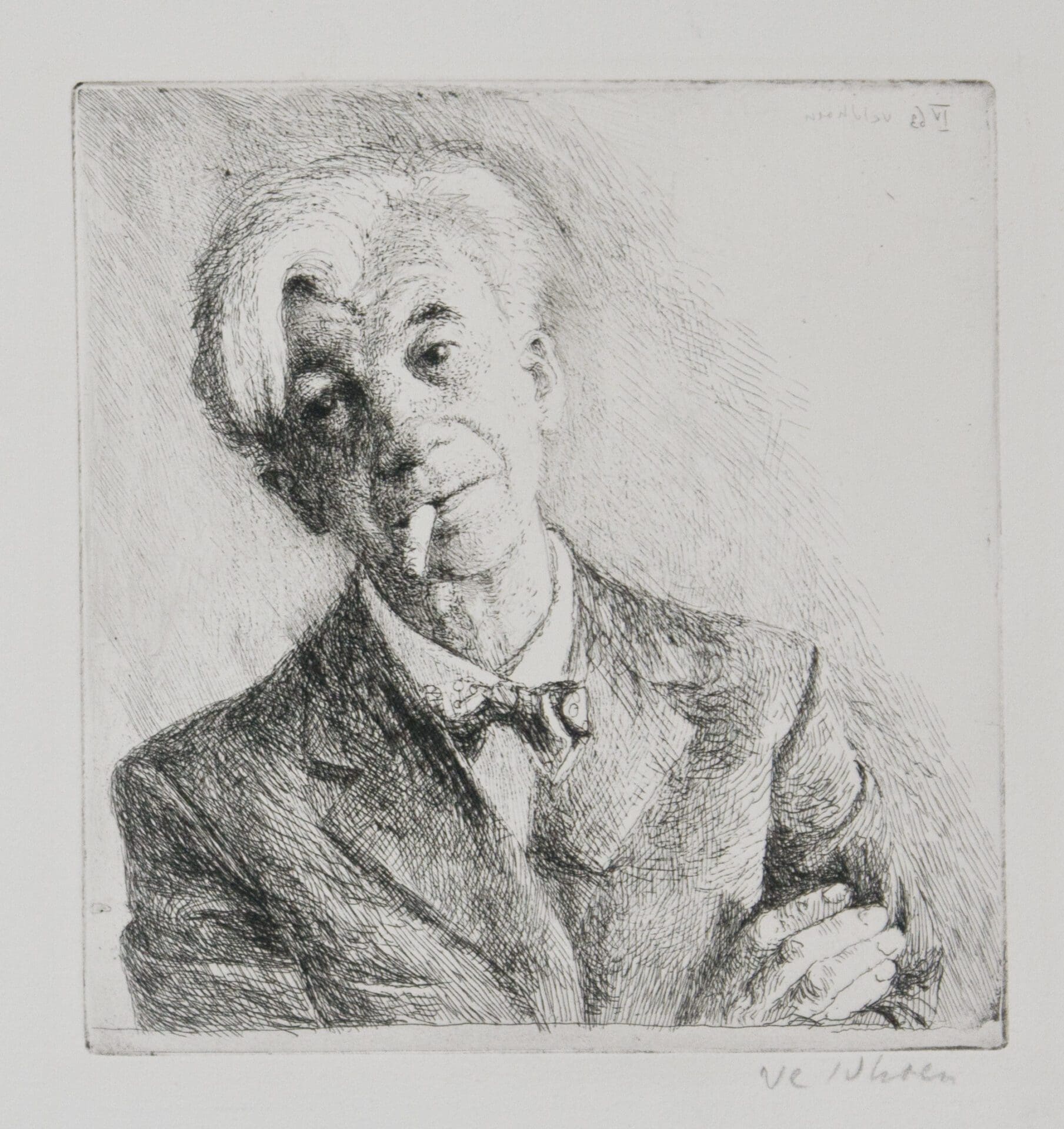

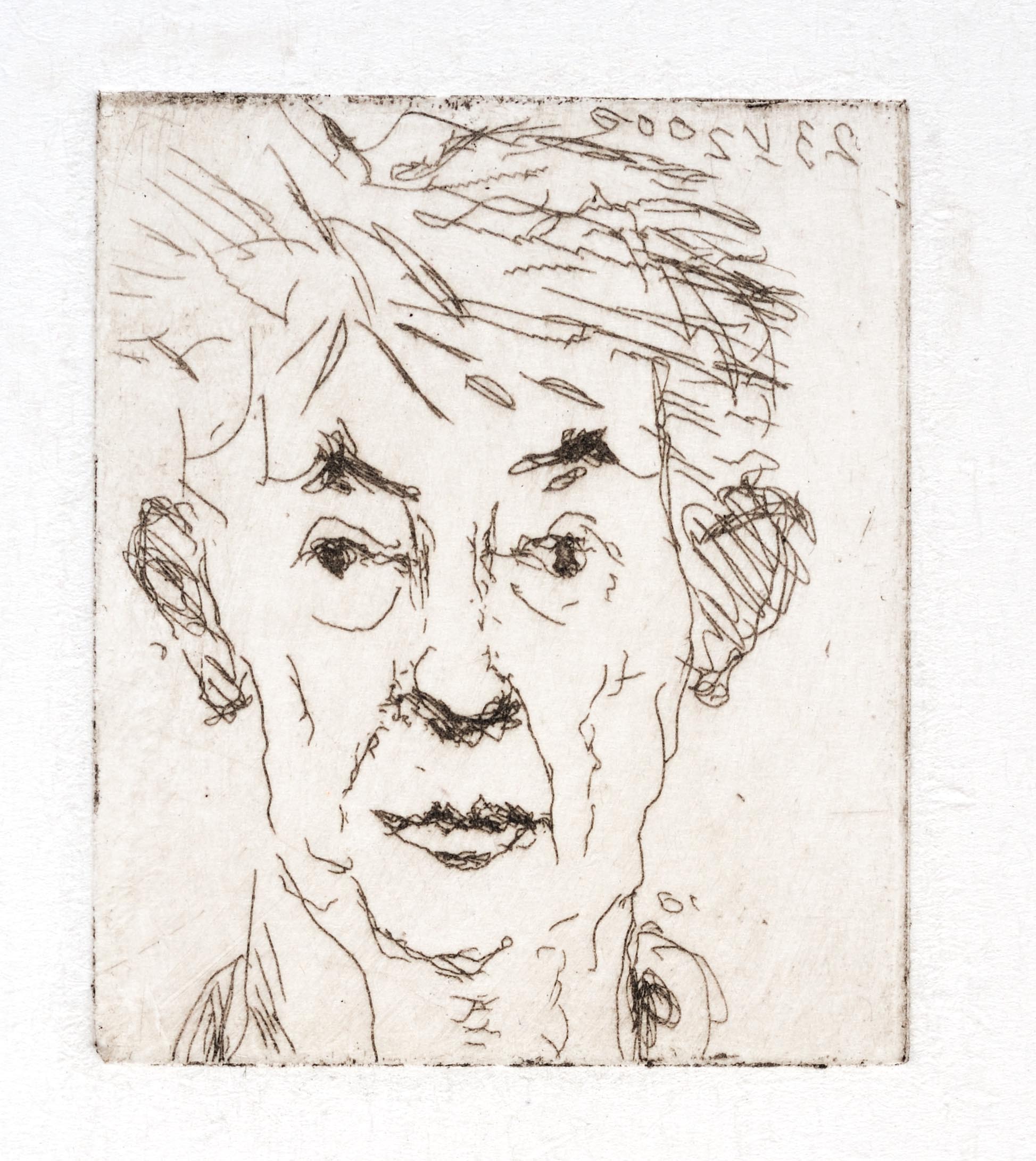

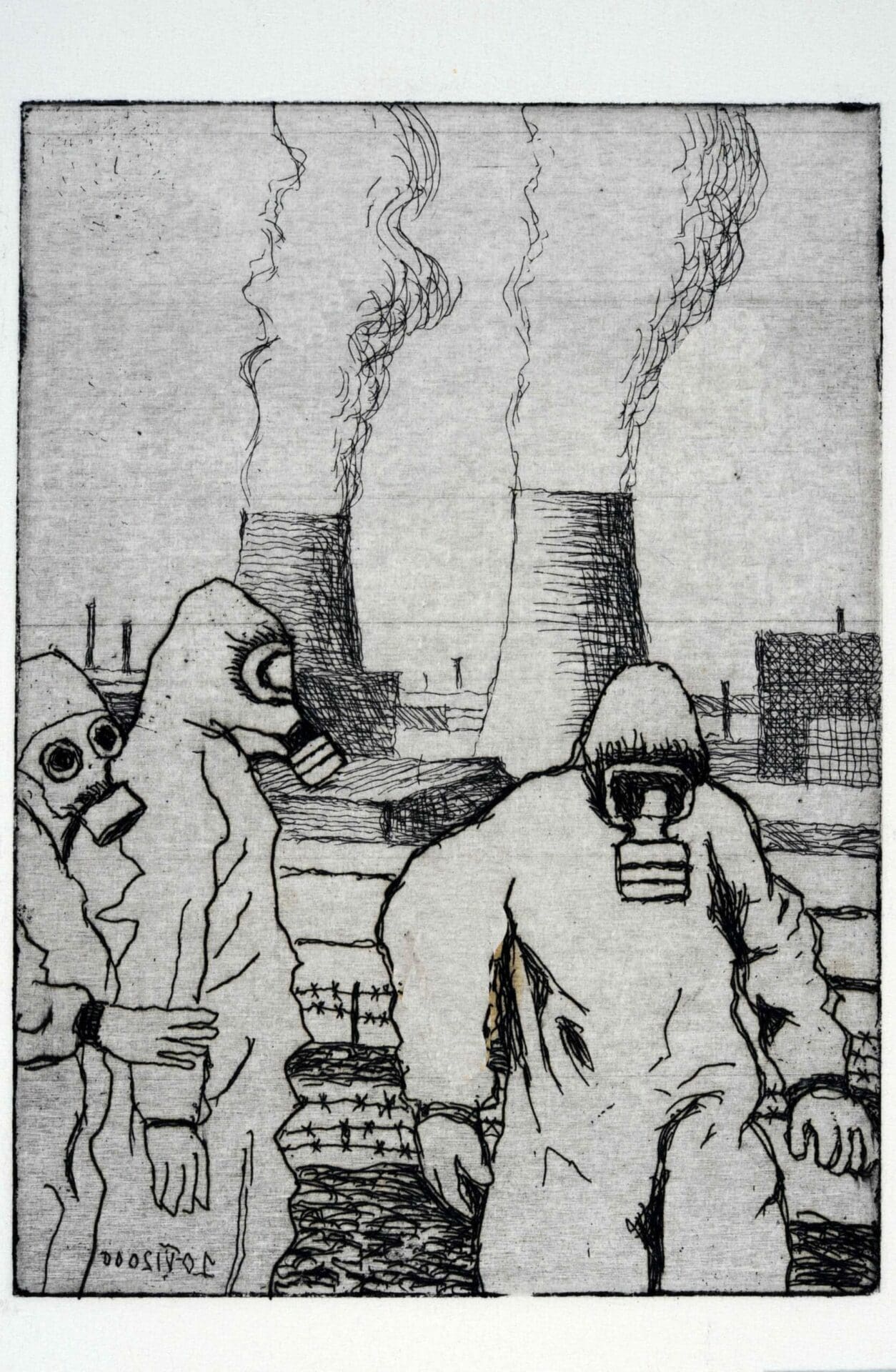

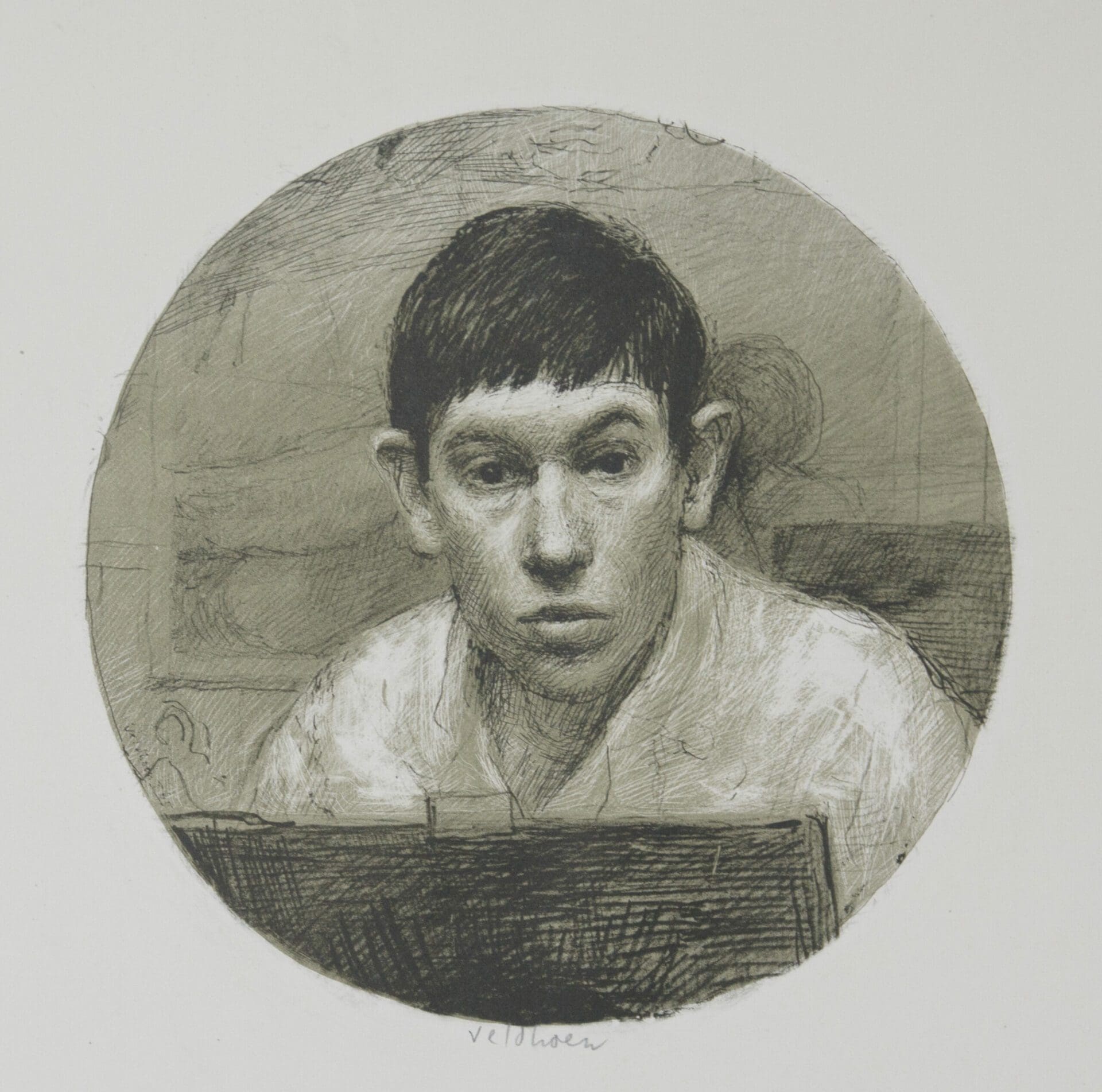

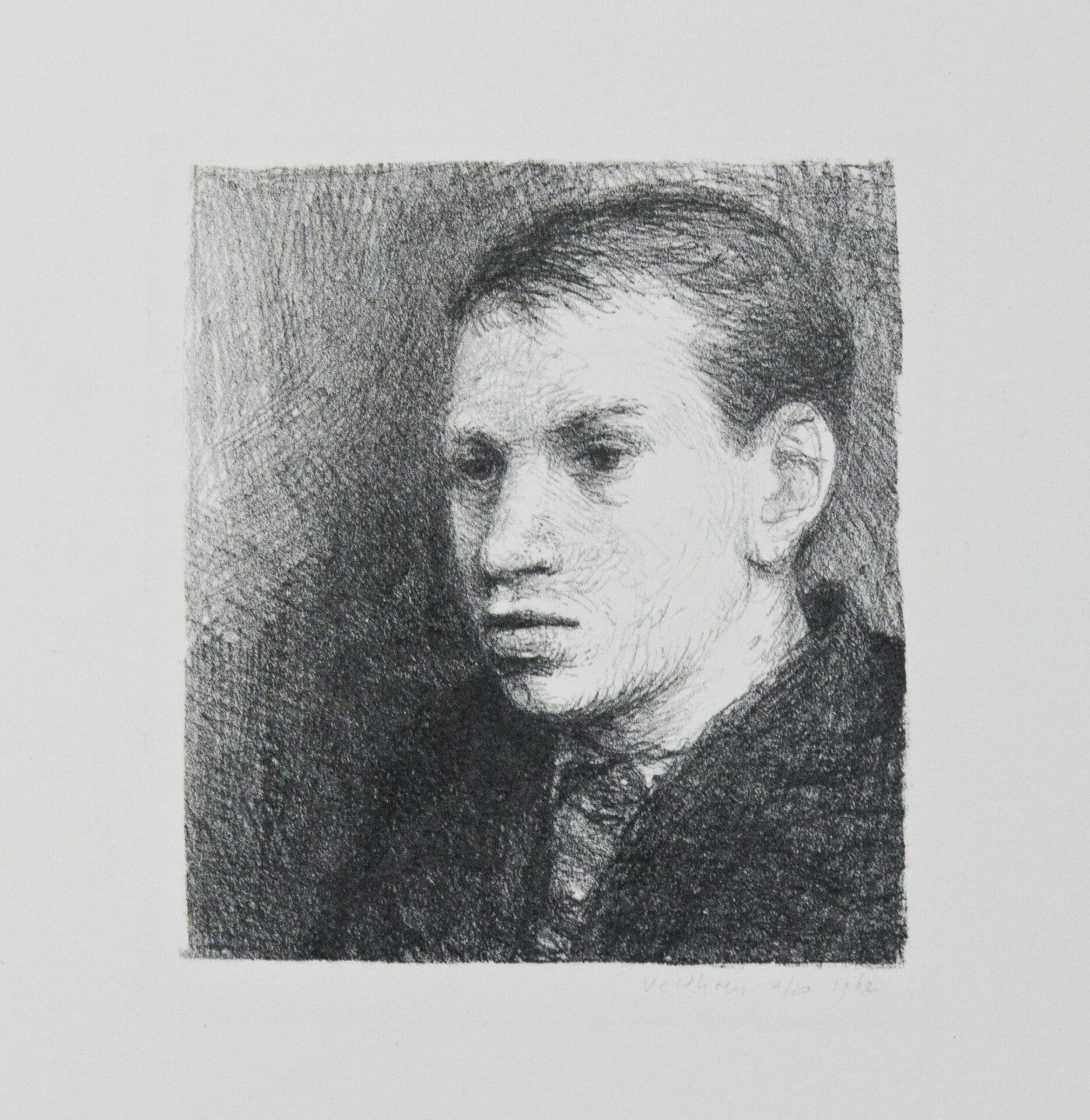

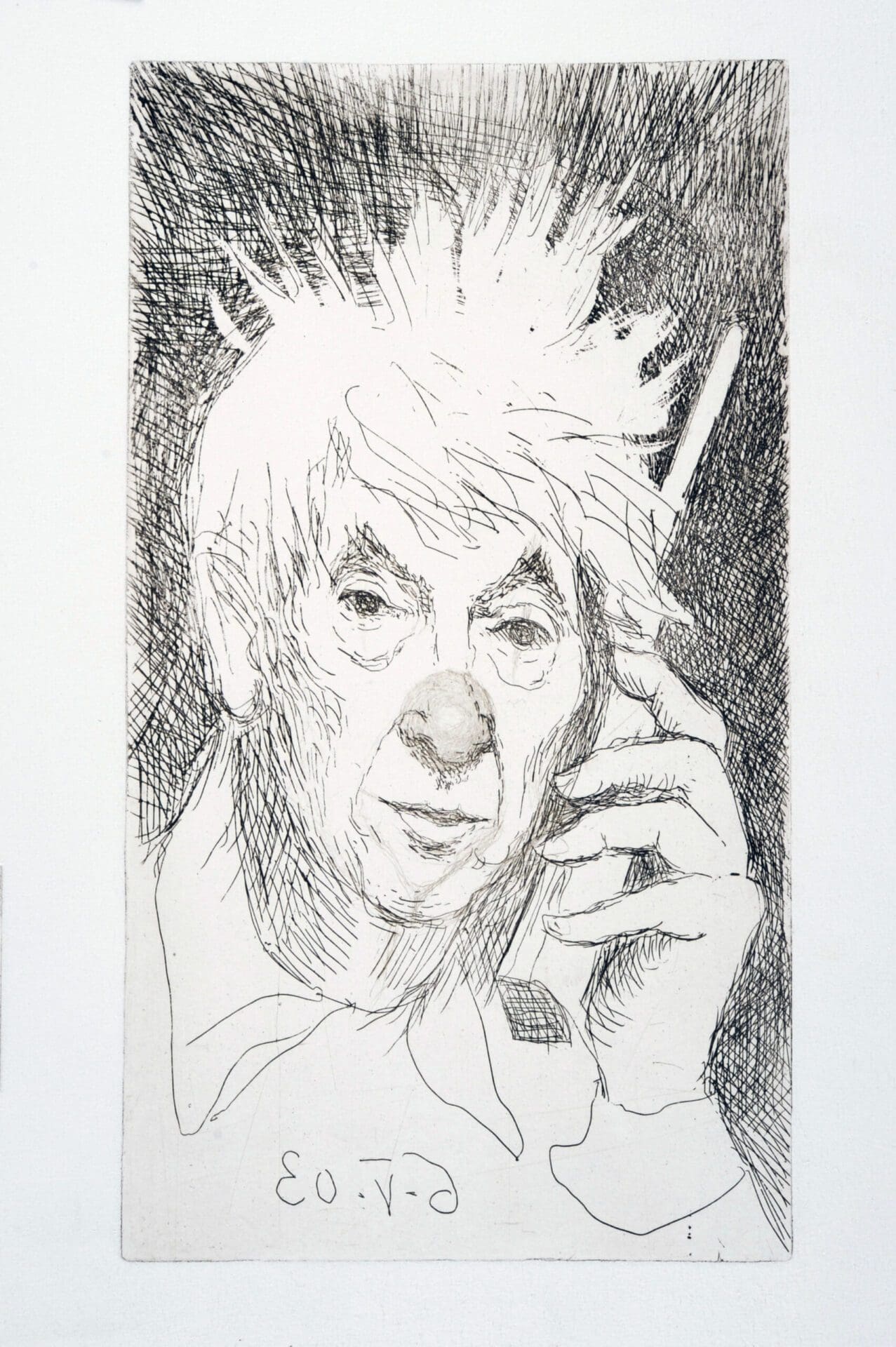

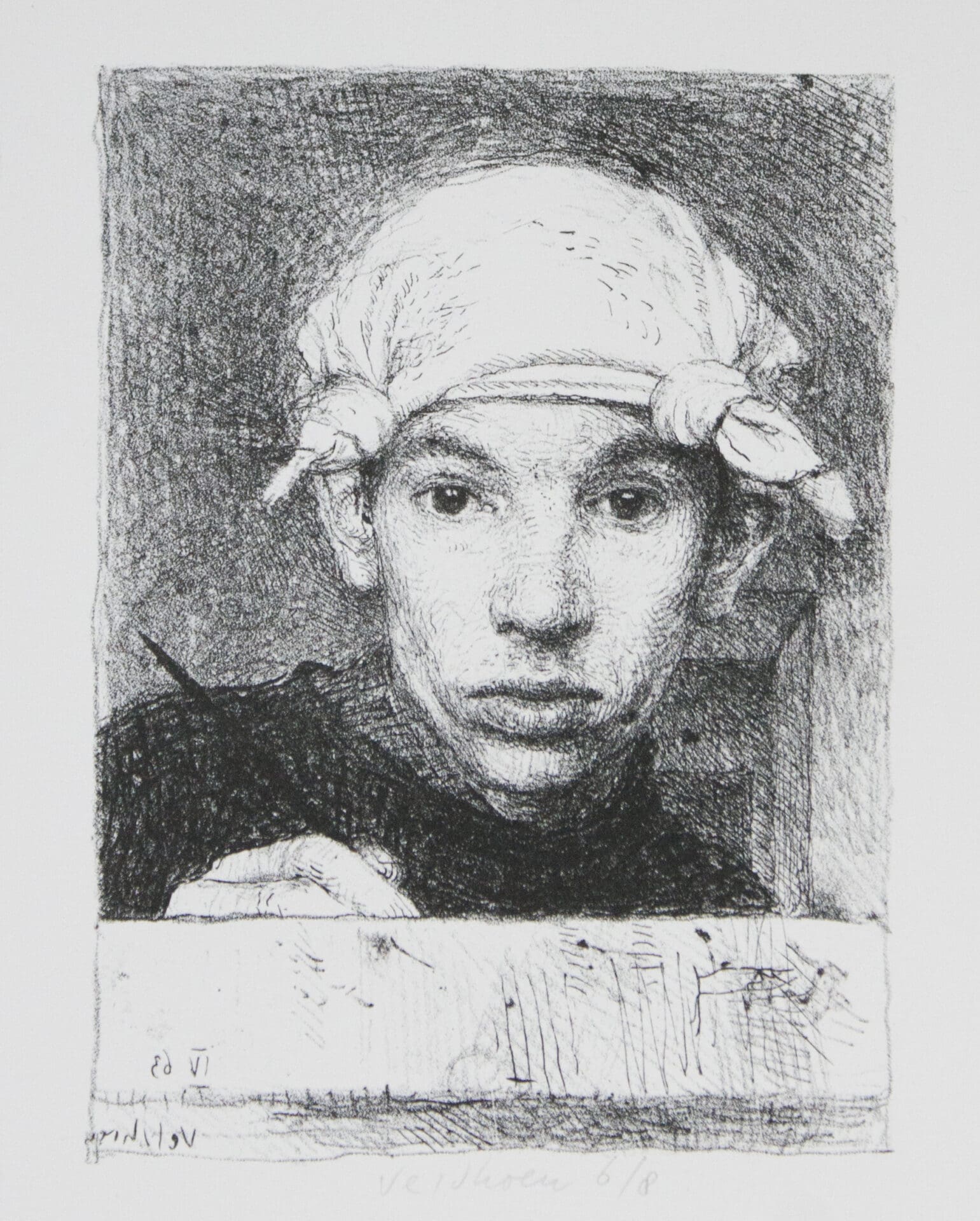

The rota prints were offered for sale by a network of shops. The prints were also sold by Robert Jasper Grootveld, who had set up a cargo bike especially for this purpose. The success was great, too great, because in no time Veldhoen had blown up his own market. Out of disappointment with this debacle, Veldhoen decided to stop making prints, but in 2000, more than thirty years later, he picked up the etching needle again. The reason was his stay of several weeks in Rembrandt’s studio, the reconstruction of which had been completed. Veldhoen started, just as Rembrandt had done, making small self-portraits. Initially, he said, he was very nervous about the historicity of the place. At first he didn’t dare to set a line, but gradually he got the hang of it. Since then he has made hundreds of etchings. Text by Ed de Heer

By Ed the Heer: At just fourteen years old, Veldhoen was admitted to training as an art teacher at the Rijksnormaalschool. He received a traditional training there, with a lot of attention to drawing from plaster, living model, perspective and composition. After four years he left school and established himself as a free artist. His great talent as an etcher was recognized almost immediately by the press and public. He bought his first etching press with the money he received from the Royal Subsidy in 1956.

As a graphic artist, Veldhoen was self-taught. His first etchings betray the influence of masters such as Van Gogh and Picasso, but it was mainly Rembrandt’s graphic work to which he was attracted. Rembrandt’s influence is already visible in his earliest work and was mainly manifested in the variations in line thickness, which he achieved by covering parts of the etching plate during the etching process.

His earliest works include the landscapes that were created in 1956 in the vicinity of Bergen and Schoorl. These often have a desolate atmosphere that arises from Veldhoen’s fascination with the contrast between abandoned bunkers and industrial complexes on the one hand and nature on the other.

Veldhoen was an artist who loved to travel. Early in his career he visited Ibiza, Spain and Africa, among others. In 1961 he received a travel grant from the Ministry of Education, Arts and Sciences that enabled him to visit Israel. On his travels, Veldhoen not only produced landscapes, but also portraits of indigenous men and women who crossed his path. He also found colourful models in Amsterdam that fascinated him.

If there is one subject to which Veldhoen remained faithful throughout his career as an etcher, it is the female nude. In addition to many anonymous models, Veldhoen mainly portrayed friends and acquaintances. The women who posed naked for him were, almost without exception, from his immediate environment. His earliest portraits have a certain abstraction, but as time progressed his portraits became more and more realistic. According to Veldhoen, the stylization of the early work arose from his unfamiliarity with the etching technique.

A special place within his oeuvre is occupied by the series with couples making love. The impetus for this also came from the work of Rembrandt, who created two explicit lovemaking scenes. Prints like these were completely wrongly labelled by moral crusaders as “stimulating the senses” and Veldhoen was even convicted in 1964 for making pornographic material. If there is one thing these prints lack, it is the complete absence of vulgar voyeurism. Veldhoen is nothing of a peeping tom. On the contrary, he succeeds time and again in an inimitable way to evoke feelings of intimacy and vulnerability in the viewer. The feeling of compassion that is so characteristic of his art is expressed very emphatically in the series of prints dedicated to women in labour and victims of street accidents. Nowhere else does Veldhoen manage to convey the feeling of loneliness and compassion as oppressively and compellingly as with these prints. According to Veldhoen, printmaking was a social art form, because it is circulation art. By printing multiple copies, the price could remain relatively low. From that perspective, it is not surprising that he welcomed the arrival of the offset rotary press with great enthusiasm. In fact, there was no difference between traditional lithography and the rotary press except that the rotary press could print huge print runs in a short time and the artist no longer had to draw on a heavy stone, but on a light aluminium plate that, once ready, was stretched onto a cylinder.

The rota prints were offered for sale by a network of shops. The prints were also sold by Robert Jasper Grootveld, who had set up a cargo bike especially for this purpose. The success was great, too great, because in no time Veldhoen had blown up his own market. Out of disappointment with this debacle, Veldhoen decided to stop making prints, but in 2000, more than thirty years later, he picked up the etching needle again. The reason was his stay of several weeks in Rembrandt’s studio, the reconstruction of which had been completed. Veldhoen started, just as Rembrandt had done, making small self-portraits. Initially, he said, he was very nervous about the historicity of the place. At first he didn’t dare to set a line, but gradually he got the hang of it. Since then he has made hundreds of etchings. Text by Ed de Heer

Continue reading